At the Institute for the Future's 2011 Ten Year Forecast event in late March, I presented a long talk on ways in which evolutionary and ecological metaphors could inform our understanding of systemic change. The head of the Ten Year Forecast team, IFTF Distinguished Fellow Kathi Vian, thought that the ideas it contained should get a wider viewing, and asked me to put the talk on my blog. Here it is. It's lightly edited, and only contains a fraction of the slides I used; let me know what you think.

We’ve now reached the part of the day where I’ve been asked to make your brains hurt. Don’t worry, there will be alcohol afterwards.

The first thing I’m going to do, of course, is talk about dinosaurs.

Everybody knows about dinosaurs, right? Giant, lumbering lizards that were killed off by an asteroid just when the smarter, more nimble mammals were starting to take over anyway. And everyone knows what dinosaur means as a metaphor: big, stupid, and about to be wiped out. Nobody wants to be a dinosaur.

What if I told you that all of that – all of it – was wrong?

Here’s another dinosaur:

It turns out that most dinosaurs were actually pretty small and fast, and far more closely related to today’s birds than to lizards.

Some dinosaurs we might envision as scaly monsters from the movies were likely actually feathered. It’s widely accepted, in fact, that dinosaurs didn’t all die off when that asteroid struck 65.5 million years ago — they stuck around as birds.

Oh, and one other thing.

The “age of dinosaurs” lasted 185 million years, not counting the 65 million years of dino-birds. And mammals first emerged about halfway through the “age of dinosaurs,” and were stuck scurrying around between dinosaur legs, trying to avoid being eaten.

Dinosaurs have been around, including as birds, for 250 million years. Humans, conversely, have been around in a form recognizable as Homo sapiens for only about 250 thousand years. Dinosaurs have had a thousand times more history than has Homo sapiens.

And they survived – arguably eventually thrived after – one of the biggest mass extinctions in Earth’s history. Maybe being a dinosaur wouldn’t be such a bad thing.

The story of dinosaurs is a particularly vivid example of what happens after complex systems face traumatic shocks. It’s a story of change and adaptation. And it’s one that we can learn from.

This will come as a surprise to precisely none of you, but one of the areas that I studied academically was evolutionary biology. Although I didn’t follow that path professionally, I’ve always kept my eyes open for ways in which bioscience can illuminate dilemmas we face in other areas.

There’s one concept from biology that I’ve been mulling for awhile, and I think it has quite a bit to say about our current global situation.

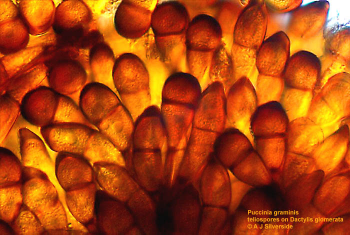

It’s an element of the concept of “ecological succession,” the term for how ecosystems respond to disruptive change. A fundamental part of that process is the “r/K selection model,” with a little r and a big K, which is a way of thinking about the reproductive strategy that living species employ within a changing environment.

Biologist E.O. Wilson came up with this concept over 30 years ago, and it’s proven to be a useful lens through which to understand ecosystems.

Species that use the “r” strategy tend to have lots of offspring, but devote little time or energy to their care. Even though most will die, the ones that survive will have a bunch of offspring of their own, hopefully carrying the same advantages that let their progenitors survive. Because these species are optimized to reproduce and spread quickly, we humans often think of them as weeds, “vermin,” and other pests.

Species that use the “K” strategy tend to have very few offspring, and devote quite a bit of time and energy to their care. Survival rates for the progeny are much higher, but the loss of an offspring is correspondingly more devastating. K species are optimized to compete for established resources, and tend to be larger and longer-lived than r species. Humans are on the K side of the spectrum, which might be why we often tend to sympathize with other K species.

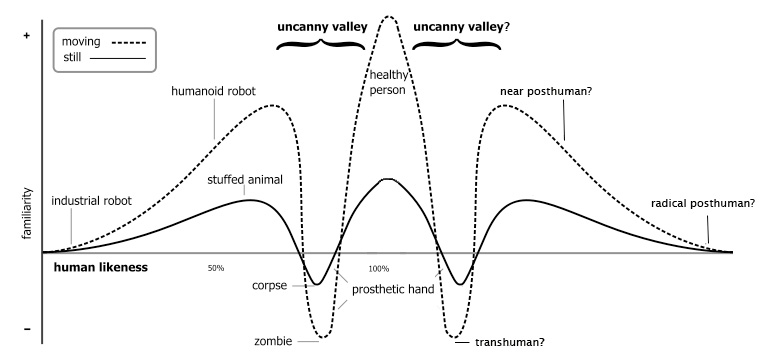

As I said, Ecological Succession is what happens when an ecosystem has been hit with a major disturbance. When various species come to re-inhabit the area, it follows a pretty standard pattern.

While conditions are still unstable, r species dominate. Although they may not be ideally suited for the changing environment, they reproduce quickly. r strategies promote rapid iteration, diversification, and a willingness to sacrifice unsuccessful offspring.

As an ecosystem returns to stability, K species start to take over. Sometimes they’ll evolve from r species, sometimes they’ll come in from other locations. Species that employ K strategies evolve to fit their environmental niche as optimally as possible, seeking out the last bit of advantage over ecological competitors.

This is the typical pattern, then: disruption, r dominance, increased stability, K dominance.

But in periods when the volatility itself is sporadic, things get weird. Think of it as “unstable instability:” disruptions happen unpredictably, with long enough periods of stasis for the normal ecological succession pattern to start to take hold – then wham! A spike of instability. But this doesn’t eliminate the K strategists; they can reemerge once stability returns.

In this kind of environment, K approaches and r approaches trade off, neither gaining dominance. This is the kind of setting that accelerates change. Arguably, extended periods of unstable instability have been engines of radical evolution. They appear at numerous points in our planet’s history, and nearly always have a major impact.

In this kind of setting, imagine the impact of a species able to shift rapidly between r and K, optimizing when possible, rapidly iterating when necessary. Such as, to pick a random example, Homo sapiens, us. We’ve been able to adapt to changing environmental conditions through technological innovation, using rapid iteration of tools to enable biological stability

The appropriate question, now, is “so what?”

The language we employ when we do foresight work is often intensely metaphorical. We focus on events yet to fully unfold, new processes overshadowed by legacies, and weak signals amidst the noise of the now. And because of this, we often find ourselves reaching for familiar concepts that parallel the story we’re trying to tell.

As I suggested earlier, the r/K selection and ecological succession models offer us some insights into what’s happening the broader global political economy.

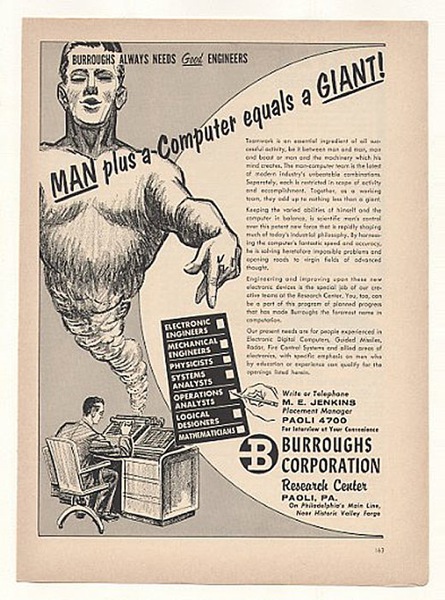

Human enterprises, whether business or government, civil or military, aren’t precisely biological species, but you can see numerous historical parallels to the ecological succession logic. The traumatic chaos of World War Two, with its vicious, rapidly-evolving competition between myriad nations, becomes the long stability of the Cold War era, dominated by two superpowers. Or, less bloody, think of the rapid churn of Silicon Valley startups trying to take advantage of a new innovation, and eventually settling into a small number of dominant players.

Time and again, disruptive events lead to periods of experimentation and diversity, which over time crystallize into more stable institutions. But if that was the extent of the metaphor, it might be of passing interest, and not of much value.

It’s the periods of unstable instability, where r and K make strange bedfellows, that pulls us in.

A useful example is the era of the late 1800s to early 1900s. There was instability, to be sure, but it was matched by periods of recovery and growth – but none of it proved able to last.

And alongside these economic and political convulsions came an enormously fruitful era of technological and social innovation. Much of the technology that so dominates our day-to-day lives that we even sometimes stop thinking of it as technology – airplanes, automobiles, air conditioning, electricity to the home, the incandescent light bulb, and so on – emerged in the period between 1880 and 1920.

So, too, did social transformations like the labor movement, the progressive model of governance, and, in the US, women’s suffrage.

I believe that there’s a good case to be made that we’re now in a similar era of unstable instability. Disruptions, when they hit, are intense, but there’s an equally powerful drive to stabilize. Innovations arise across a spectrum of technologies, but quickly become old news. There are major conflicts over social change. Both recoveries and chaos have strong regional and sectoral dimensions, and can flare up and die off seemingly without notice.

It would be dangerous to rely on strategies – reproductive or otherwise – that assume the continuation of either stability or instability. This period of unstable instability has been with us for at least the last decade, and will very likely continue for at least another decade more.

And this suggests that neither relying upon scale and incumbency nor relying upon rapid-fire iteration will succeed as fully and as dependably as we might wish. We can’t depend on either the garage hacker or the global corporation to push us to a new phase of history. It’s going to have to be something that manages to combine elements of both flexible experimentation and long-term strategy. Something that puts r in service of K.

This doesn’t mean that r is less important than K; we could just as easily call it “K enabling r.” Either way, it comes down to strategies that take advantage of scale and diversity, that allow both long-shot experimentation and quick adoption of innovation. Decentralized, but collaborative.

Strategies, in other words, that are resilient.

Resilience is a concept we think about quite a bit at IFTF, and if you’ve been involved in engagements with us over the past couple of years, you have probably heard us talk about it. It’s the ability of a system to withstand shocks and to rebuild and thrive afterwards. We believe that it will be a fundamental characteristic of success in the present decade, and Kathi will talk more about it tomorrow.

But from the ecological perspective, resilience interweaves r and K, containing elements that we might consider to be “r” in nature , as well as elements we’d consider to be “K.”

Resilience is the goal. r in service of K is the path.

Now, I said a moment ago that this “unstable instability” is likely to last for at least another decade. I’m sure we could all spend the next hour coming up with reasons why that might be so, but one that I want to focus on for a bit is climate disruption. In many respects, climate disruption is the ultimate unstable instability system.

Climate disruption is something that comes up in nearly all of our gatherings these days, and I don’t think I need to reiterate to this audience the challenges to health, prosperity, and peace that it creates.

We’ve spent quite a bit of time over the last few Ten Year Forecasts looking at different ways we might mitigate or stall global warming. Last year, we talked about carbon economies; the year before that, social innovation through “superstructures.” In 2008, geoengineering. This year, I want to take yet another approach. I want to talk about climate adaptation.

I say that with some trepidation. Adaptation is a concept that many climate change specialists have been hesitant to talk about, because it seems to imply that we can or will do nothing to prevent worsening climate disruption, and instead should just get ready for it. But the fact of the matter is that our global efforts at mitigation have been far too slow and too hesitant to have a near-term impact, and we will see more substantial climate disruptions in the years to come no matter how hard we try to reduce carbon emissions. This doesn’t mean we should stop trying to cut carbon; what it does mean is that cutting carbon won’t be enough.

But adaptation won’t be easy. It’s going to require us to make both large and small changes to our economy and society in order to endure climate disruption more readily. That said, simply running down a checklist of possible adaptation methods wouldn’t really illuminate just how big of a deal adaptation would be. We decided instead that it would be more useful to think through a systematic framework for adaptation.

Our first cut was to think about adaptations in terms of whether they simplify systems – reducing dependencies and thereby hopefully reducing system “brittleness” – or make systems more complex, introducing new dependencies but hopefully increasing system capacity.

Simplified systems, on the whole, tend to be fairly local in scale. But reducing dependencies can also reduce influence. Simplification asks us to sacrifice some measure of capability in order to gain a greater degree of robustness. It’s a popular strategy for dealing with climate disruption and energy uncertainty; the environmental mantra of “reduce, reuse, recycle” is a celebration of adaptive simplification.

Adaption through complexity creates or alters interconnected systems to better fit a changing environment. This usually requires operating at a regional or global scale, in order to take advantage of diverse material and intellectual resources. Complex systems may have increased dependencies, and therefore increased vulnerabilities, but they will be able to do things that simpler systems cannot.

So that’s the first pass: when we think about adaptation, are we thinking about changes that make our systems simpler, or more complex?

But here’s the twist: the effectiveness of these adaptive changes and the forms that they take will really depend upon the broader conditions under which they’re applied. We have to understand the context.

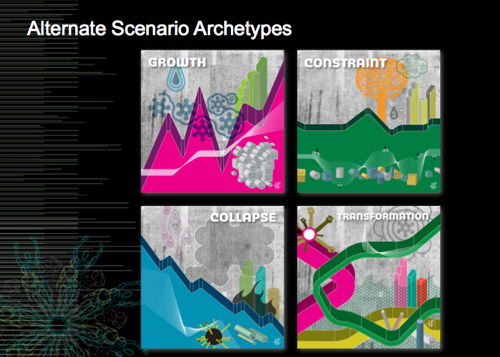

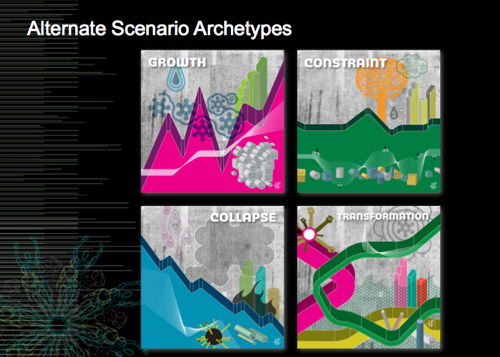

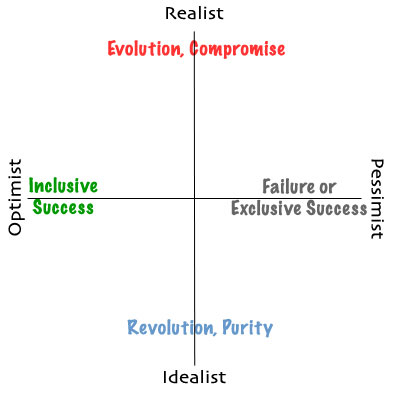

At last year’s Ten-Year Forecast, we introduced a tool for examining how choices vary under different conditions. It’s the “alternate scenario archetype” approach, and it offers us a framework here for teasing apart the implications of different adaptive strategies. If you were here last year, you’ll recall that the four archetypes are Growth, Constraint, Collapse, and Transformation. These four archetypes give us a basic framework to understand the different paths the future might take.

But let’s also apply the ecosystem thinking I was talking about earlier. With this in mind, we can see Growth and Collapse as aspects of the standard ecological succession model: Growth supports K strategy dominance, until we get a major disruption leading to Collapse, which supports r strategy dominance until we return to Growth. As it happens, while they may not use this exact language, many of the long-term cycle theories in economist-land map to this model.

Constraint and Transformation, however, seem more like unstable instability scenarios.

Both Constraint and Transformation have quite a bit in common. Both can be seen as being on the precipice of either growth or collapse, and needing just the right push to head down one path or the other. At the same time, both will contain pockets of growth and collapse, side by side, emerging and disappearing quickly. In both, previously well-understood processes no longer seem to work as well, yet there’s enough that remains functional and understandable that the world doesn’t simply spin apart. For both, the underlying systems are in flux.

With Constraint, the result is a reduced set of options. The uncertainty and churn limit what you can do.

With Transformation, the result is the emergence of new models and new opportunities.

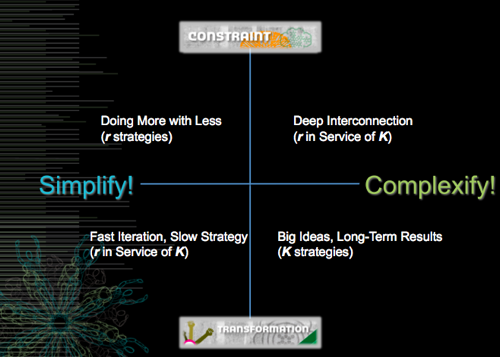

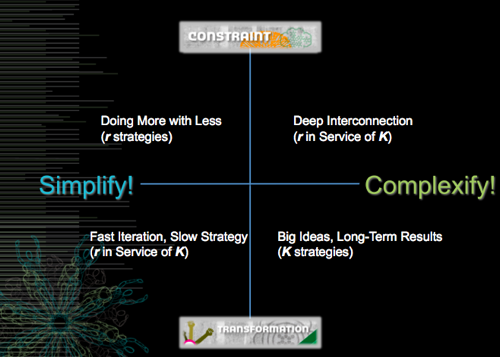

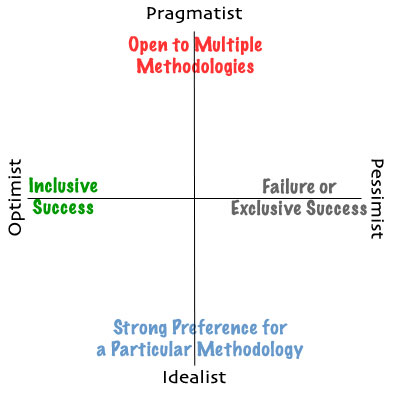

So we have two adaptive strategies – simplify and complexify – and two conditions of “unstable instability” – constraint and transformation. What do you do when you have two variables? You make a matrix!

Ah, the good old two-by-two matrix. So let’s put up the conditions, and the strategies. What happens when we combine them?

In many ways, Constraint and Simplification go hand-in-hand, giving us a world of doing more with less. Smaller scale, fewer resources, and a need for cheap experimentation: this is very much an “r” world.

Similarly, Transformation and Complexification are also common partners, resulting in a world focused on big ideas and long-term results. The potential is here for major changes, but failures can be catastrophic: it’s a classic “K” world.

The less-common combinations, however, prove pretty interesting.

When you link Constraint and Complexification , you get a world of deep interconnection: lots of small components in dense networks. There’s quite a bit of interdependence, but no one element is a potential “single point of failure.” This is an “r in service of K” world.

And when Transformation and Simplification come together , you get a world of fast iteration and slow strategy: numerous projects and experiments functioning independently, with loose connections but a long-range perspective. This, too, is an “r in service of K” world.

Okay.

Remember, I said earlier that foresight relies on intensely metaphorical language. You might not have expected the metaphors to be quite that intense, however. So here’s the takeaway:

Adaptation can take multiple forms, but more importantly, the value of an adaptation depends upon the conditions in which it is tried. Just because an adaptive process worked in the past doesn’t mean that it will be just as effective next time. But there are larger patterns at work, too. If you can see them early enough, you can shape your adaptive strategies in ways that take advantage of conditions, rather than struggle against them.

But here’s the crucial element: it looks very likely that we’re in a period where the large patterns we’ve seen before aren’t working right.

Instead, we’re in an environment that will force swift and sometimes frightening evolution. Businesses, communities, social institutions of all kinds, will find themselves facing a need to simultaneously experiment rapidly and keep hold of a longer-term perspective. You simply can’t expect that the world to which you’ve become adapted will look in any way the same – economically, environmentally, politically – in another decade.

As a result, you simply can’t expect that you will look in any way the same, either.

The asteroid strikes. The era of evolution is upon us. It’s now time to watch the dinosaurs take flight.

Time for another thought experiment. Or, rather, a puzzle without a good answer yet.

Time for another thought experiment. Or, rather, a puzzle without a good answer yet. Thought experiment: imagine you've been taken, somehow, and dropped into a big city in another place, with comparable technological and economic development, somewhere you don't speak the language. Here's the twist: it's also time travel. How long would it take you to notice that you've been shifted in time as well as space?

Thought experiment: imagine you've been taken, somehow, and dropped into a big city in another place, with comparable technological and economic development, somewhere you don't speak the language. Here's the twist: it's also time travel. How long would it take you to notice that you've been shifted in time as well as space? One of my favorite posts from my time here at Open the Future has to be

One of my favorite posts from my time here at Open the Future has to be

If there's a common trope about "futurism," it's that it gets everything wrong.

If there's a common trope about "futurism," it's that it gets everything wrong.

Cyberculture legend

Cyberculture legend

"We are as gods and might as well get good at it." -- Stewart Brand, the

"We are as gods and might as well get good at it." -- Stewart Brand, the  You can find the manifesto of the group (in Spanish)

You can find the manifesto of the group (in Spanish)

When people learn that I'm a professional futurist*, almost invariably the immediate response is the question "what predictions have you gotten right?"

When people learn that I'm a professional futurist*, almost invariably the immediate response is the question "what predictions have you gotten right?" What leapt out at me, conversely, was the video's prescience about how a digital newspaper would function: the use of the conventional newspaper form as a recognized interface; the seamless leap from headline to full story; the use of animation and video integrated with the text; the lack of limits on space; even the need to pay for the news via advertising. It was clear that the designers of the tablet newspaper in the video had given careful thought to the evolution not just of digital hardware, but user interfaces. Remember, in 1994 the web still looked like the image to the right.

What leapt out at me, conversely, was the video's prescience about how a digital newspaper would function: the use of the conventional newspaper form as a recognized interface; the seamless leap from headline to full story; the use of animation and video integrated with the text; the lack of limits on space; even the need to pay for the news via advertising. It was clear that the designers of the tablet newspaper in the video had given careful thought to the evolution not just of digital hardware, but user interfaces. Remember, in 1994 the web still looked like the image to the right.

If you watched the American

If you watched the American

My friend Stowe Boyd, consultant and provocateur,

My friend Stowe Boyd, consultant and provocateur,  You might remember the story of old

You might remember the story of old

The

The

Failure happens. Strategic plans that don't take into account the possibility of failure -- and propose pathways to adaptation or recovery -- are at best irresponsible, at worst immoral. The war in Iraq offers an obvious example, but the potential for failure in our attempts to confront global warming* may prove to be an even greater crisis. This is why I'm so adamant about the need to study the potential for

Failure happens. Strategic plans that don't take into account the possibility of failure -- and propose pathways to adaptation or recovery -- are at best irresponsible, at worst immoral. The war in Iraq offers an obvious example, but the potential for failure in our attempts to confront global warming* may prove to be an even greater crisis. This is why I'm so adamant about the need to study the potential for

I've long been a proponent of the core Viridian argument that "making the invisible visible" (MTIV) -- illuminating the processes and systems that are normally too subtle, complex or elusive to apprehend -- is a fundamental tool for enabling behavioral change. When you can see the results of your actions, you're better able to change your actions to achieve the results you'd prefer. I've come to understand, however, that it's not enough to make the invisible visible; you also have to make it meaningful.

I've long been a proponent of the core Viridian argument that "making the invisible visible" (MTIV) -- illuminating the processes and systems that are normally too subtle, complex or elusive to apprehend -- is a fundamental tool for enabling behavioral change. When you can see the results of your actions, you're better able to change your actions to achieve the results you'd prefer. I've come to understand, however, that it's not enough to make the invisible visible; you also have to make it meaningful. Late last month, the UK's environment secretary, David Milbrand, proposed putting

Late last month, the UK's environment secretary, David Milbrand, proposed putting  I like Stewart Brand, and he and I seem to get along pretty well. I first met him at GBN a decade ago, and I run into him fairly often at a variety of SF-area futures-oriented events.

I like Stewart Brand, and he and I seem to get along pretty well. I first met him at GBN a decade ago, and I run into him fairly often at a variety of SF-area futures-oriented events. The "Good Ancestor Principle" is based on a challenge posed by Jonas Salk:

The "Good Ancestor Principle" is based on a challenge posed by Jonas Salk:

BY CLICKING "I AGREE" YOU ACCEPT THE PROVISIONS OF THIS LICENSE.

BY CLICKING "I AGREE" YOU ACCEPT THE PROVISIONS OF THIS LICENSE. Lots of nano-news over the past week or two -- and most of it good!

Lots of nano-news over the past week or two -- and most of it good! Muscles Made of Yarn: One potential application in the body of carbon nanotubes may be in artificial muscle fibers. University of Texas at Dallas researchers have come up with a way to use carbon nanotubes, would together like yarn, as electro-chemical actuators acting essentially like muscles. According to

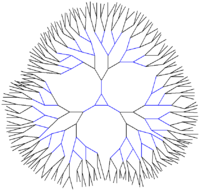

Muscles Made of Yarn: One potential application in the body of carbon nanotubes may be in artificial muscle fibers. University of Texas at Dallas researchers have come up with a way to use carbon nanotubes, would together like yarn, as electro-chemical actuators acting essentially like muscles. According to  Dendrimers are

Dendrimers are  An offhand comment at the Institute for the Future workshop yesterday sent me spiraling off in a new direction. Tom Arnold, Chief Environmental Officer of

An offhand comment at the Institute for the Future workshop yesterday sent me spiraling off in a new direction. Tom Arnold, Chief Environmental Officer of  It's the classic dilemma of both foresight and environmental consulting: how do you get the people with the power to act to pay attention? Political leaders rarely pay sufficient attention to issues of systemic sustainability and planning for long-term processes, at least before events reach a crisis. There are numerous reasons why this might be, ranging from election cycles to crisis "triage" to politicians not wanting to institute programs for which they won't be around to take credit. It's nearly as difficult to get leaders to pay attention to complex systems, with superficially different but deeply-connected issue areas. If you were to try to bring together political, business and community leaders for a day-long discussion of, say, what life might be like at the midpoint of this century, with a focus on environmental sustainability coupled with economic, cultural and demographic demands, how much support do you think you'd get?

It's the classic dilemma of both foresight and environmental consulting: how do you get the people with the power to act to pay attention? Political leaders rarely pay sufficient attention to issues of systemic sustainability and planning for long-term processes, at least before events reach a crisis. There are numerous reasons why this might be, ranging from election cycles to crisis "triage" to politicians not wanting to institute programs for which they won't be around to take credit. It's nearly as difficult to get leaders to pay attention to complex systems, with superficially different but deeply-connected issue areas. If you were to try to bring together political, business and community leaders for a day-long discussion of, say, what life might be like at the midpoint of this century, with a focus on environmental sustainability coupled with economic, cultural and demographic demands, how much support do you think you'd get? The next five days will see a potentially interesting -- at least to me -- intersection of a variety of important dynamics I've been following closely.

The next five days will see a potentially interesting -- at least to me -- intersection of a variety of important dynamics I've been following closely. Last week, at a

Last week, at a  Bruce Sterling did me the honor of

Bruce Sterling did me the honor of  David Brin wrote a

David Brin wrote a  Andrew Jackson Wickline, my grandfather, the man I was named for, died three years ago, shortly before Memorial Day; a veteran of World War II, he was given a military service on Memorial Day itself, 2003.

Andrew Jackson Wickline, my grandfather, the man I was named for, died three years ago, shortly before Memorial Day; a veteran of World War II, he was given a military service on Memorial Day itself, 2003. I look at the people in my grandfather's photos, and wonder: did they know they were remaking the world? Were these simply snapshots to them, vacation photos with an edge, or did they recognize that they were documenting their roles in a monumental political transformation? How would our understanding of the second world war differ if everyone had carried a camera, not just one person out of hundreds, or thousands?

I look at the people in my grandfather's photos, and wonder: did they know they were remaking the world? Were these simply snapshots to them, vacation photos with an edge, or did they recognize that they were documenting their roles in a monumental political transformation? How would our understanding of the second world war differ if everyone had carried a camera, not just one person out of hundreds, or thousands?

I've been thinking quite a bit lately about how we make long-term decisions. The trite reply of "poorly" is perhaps correct, but only underscores the necessity of coming up with reliable (or, at least, trustable) mechanisms for thinking about the very long tomorrow. Many of the biggest crises likely to face human civilization in the 21st century have important long-term characteristics, and our relative inability to think in both complex and actionable ways about slow processes may be our fundamental problem.

I've been thinking quite a bit lately about how we make long-term decisions. The trite reply of "poorly" is perhaps correct, but only underscores the necessity of coming up with reliable (or, at least, trustable) mechanisms for thinking about the very long tomorrow. Many of the biggest crises likely to face human civilization in the 21st century have important long-term characteristics, and our relative inability to think in both complex and actionable ways about slow processes may be our fundamental problem.