The following is the text of the talk I gave this morning at the International Association for Public Participation conference in Montreal, Canada. Where useful or necessary, I've added the relevant slide images. Updated: added links.

My name is Jamais Cascio, and I'm a foresight specialist by trade -- that's a fancy way of saying "futurist." Now, when most of you hear the word "futurist," you probably imagine the guys telling us about personal jetpacks and honeymoons in orbit, or maybe the marketing types eager to identify new trends and fads. I like to think that I fall into a third category, however: futurists who take seriously the call to serve as society's radar, giving us all early warnings of big changes ahead.

I know you've heard a bit already about the increasingly critical role that Internet technologies play in the world of public participation. Whether we think of this new world as "Citizens 2.0" or some less catchy phrase, it's clear that the emergence of these network-empowered tools is serving as a catalyst for some important changes in how we relate to each other, our governments and -- most importantly -- our civil societies.

Think of it as the emergence of a new participatory culture.

And like many new cultures, it has its own language. The terms you see here are some of the jargon from the Internet movement sometimes referred to as the "open economy" or "Web 2.0." This movement is the technological engine of the new participatory culture. Some of the terms are fairly self-explanatory, while others may sound like some crazy moon language.

But they all have something important in common. These terms, and the tools they describe, all build on the concept that working together in ad-hoc, emergent ways, we can accomplish far more than we can either as individuals or as part of some top-down hierarchy. These are all ways of allowing interested, eager participation in efforts that would be too big for any single person, and too "out of control" (in Kevin Kelly's phrase) for any traditional organization.

This list covers some of the characteristics of this emerging participatory culture.

- Collaboration

- Distribution

- Networks over hierarchies

- Transparency

- Ownership of reputation vs. ownership of property

- Ideas are catalysts for more ideas

- Technology-enabled, not technology-focused

These aren't "rules" so much as descriptive properties, recurring themes across the models, tools and ideas that make up the new world. Some are likely familiar -- people have been talking about the power of collaboration and networks for some time -- and some are likely less so.

The last point on this list, "technology-enabled, not technology-focused," is the most subtle, but I think the most important point to understand. You've undoubtedly heard a great deal about different technologies so far, and I'm going to be talking about more of them. But the key idea here isn't simply how cool the toys, gadgets and online widgets are, it's what people can do with them.

Take, for example, open source. You're probably familiar with the term as something related to computers. The operating system Linux, the web server software Apache, and the web browser program Firefox are three of the better-known pieces of open source software.

The underlying logic of open source is straightforward: don't just give someone a new application or product, give them the instructions -- the "source code" -- for how to make it, too. Allow the recipients to modify it as they deem necessary, to fix problems or to fit their local requirements, and adopt the improvements other participants have contributed. Finally, let them give away their own changed versions -- with the only rule being that they have to pass along their own source code, too.

There's obvious idealism in this model, but it has worked surprisingly well in the world of software. Open source programs are widely used, and many are considered to be the best in their categories. Open source has gained quite a bit of traction in the developing world as a way of simultaneously building up a technological infrastructure for little money, while offering the opportunity for users of software to become creators, as well.

Moreover, this model -- give it away, allow changes, adopt the best, repeat -- has come to be used in other realms, from architectural design to grassroots organizing.

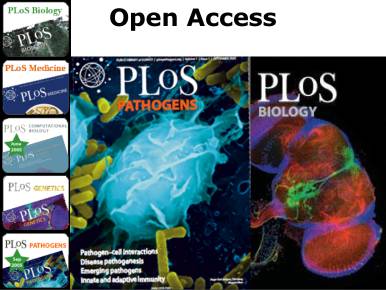

Open source as an engine of creation isn't alone. The world of scientific publishing has been shaken up in recent years with the advent of Open Access. It's a new term for a familiar concept: the publication of scientific research for free, knowing that the broader availability of the research will allow more people around the world to participate in further scientific discovery. It's a return to the idea of science as global exploration, not patent acquisition.

The Public Library of Science journals, shown here, have been at the vanguard of this movement, but even the more traditional scientific publishing houses have begun to use the open access model in limited degrees. The argument behind open access is hard to dispute: science is a collaborative process, made stronger by more people engaged in the practice. The fewer the barriers to participation, the better.

Even more radical is the idea of "open source science," where it's not simply the results that get published freely, but the instructions for the underlying research and development. The most energetic work in this realm has been in the biomedical disciplines, where the results have direct social applications. This has not been without controversy; some open source science projects, like the Biological Innovation for Open Society group, actively promote the dissemination of biotechnology know-how. Unsurprisingly, some people fear the misuse of this information.

Open source science advocates argue that this kind of scientific transparency actually makes us safer, rather than putting us at greater risk. They note that restrictions and proprietary control haven't proven terribly good at preventing misuse of scientific and technological breakthroughs in the past, but have made it harder for affected populations to get the information necessary to combat the problems that arise from misuse. Just like open source software has fewer security flaws than commercial code, they suggest, open source science will be safer because of the presence of the expanding community able to fix problems that might occur.

These three concepts -- share the code; share the results; share the applications -- are the early indicators of a participatory earthquake in the making.

Of course, it's not just scientists and engineers that work in the world of participatory innovation. Tens of millions of people around the globe, likely including many in this room, have begun to experiment with weblogs, putting up their ideas on the web for everyone to see. Weblogs, or blogs, go beyond simple digital diaries: their power comes from their links to other sites, which immediately provide documentation and resources beyond what a single person could produce, as well as from the emergent communities participating in the blogs, turning conversation into action.

A growing number of blogs have tapped into their communities to provide support for issues they deem important, from the environment to free speech. Last week's election in the US was a visible example of the blogging world flexing its muscle: Daily Kos, one of the sites shown here, was a catalyst for bringing attention, funding and support to dozens of obscure candidates around the country -- nearly all of whom won their races. The Kos site often talks about the power of the "netroots" (as opposed to grassroots), and indeed that power is growing.

Not everyone has the time or inclination to build a weblog. That doesn't leave them out of the new participatory culture, however. Wikis are another collaborative information tool open to just about everyone online. Wikis are web pages that can be edited by the people reading the site. This is a simple but startlingly powerful concept: no longer are you a passive reader; if you have something to add to a document, wikis allow you to do so. Organizations eager to take advantage of the power of participatory culture have begun to adopt wikis in great abundance, from social investment groups to environmentalist resources; even political parties -- the Green Party of Canada, for example, made its entire party platform a wiki document open to any party member to edit.

Wikipedia is probably the best-known example of a wiki in action. If you've not heard of Wikipedia before, it's simply an encyclopedia that uses a wiki model. With well over a million entries, it's one of the largest repositories of information available online. And it's an encyclopedia that anyone can edit.

You might think that this would be a recipe for chaos and vandalism, and indeed there have been some high-profile cases of people making malicious changes to pages. Less often reported, however, is the fact that these malicious changes usually get repaired within moments -- the millions of participants serve as the watchmen of the site. If that process sounds familiar, it should. It's an example of what open source science advocates claim is the primary engine of security in an open world: the collaborative action of the crowd.

Given that anyone can edit Wikipedia, without regards to expertise, you might also imagine that the quality is marginal. Certainly its traditional competitors, like Encyclopedia Britannica, seem to make that suggestion. But Nature magazine, my pick for the world's best science journal, recently compared Wikipedia's entries on a variety of scientific disciplines to those in Britannica, which is generally considered to be the best print encyclopedia around. Much to their own surprise, they found the two to be effectively equal in utility and accuracy.

Participatory online tools aren't just for information creation; they're also for communication. By far the fastest growth in online activity is in communities of interest, from social sites like MySpace to photo repositories like Flickr. Admittedly, few of these are open source, although that's slowly changing. The more important aspect of these networks is their use as engines of rapid information exchange. For a quickly-growing number of young people, these social networks, along with tools like instant messaging, have become absolutely critical forms of communication.

Such networks aren't just limited to teenagers. Similar social networking services have appeared for professional groups, political movements and parents.

Even if most of the communication that takes place in online social networks is personal, similar tools can provide a broader social information function. Increasingly, this open exchange of information has been formalized as "citizen journalism," where the members of the public serve as reporters, offering their own "first draft of history" from the scene, and working together to follow stories that the typical poorly-funded newsroom cannot.

Don't discount this as the digital equivalent of an office newsletter or small town weekly. Local analysts credit OhMyNews, a Korean citizen journalism site, with playing the key role in bringing down the previous Korean administration by uncovering corruption that the traditional media wouldn't touch. OhMyNews has now expanded to international coverage, with an English-language edition.

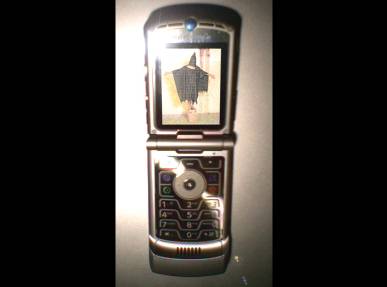

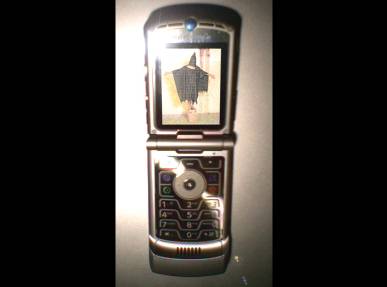

And the proliferation of cameraphones has begun to affect how news is gathered, as well. People on the scene can take pictures -- sometimes pictures that will haunt you afterwards -- and transmit them as easily as a text message. In addition, some cameraphones have come to offer video capabilities, and we're starting to see this as part of the ongoing evolution of participatory journalism.

But it's not simply the availability of cheap video cameras and cameraphones that has triggered this evolution; it's the ability of those who make the videos to put them up on the web for global access. Sites like YouTube claim millions of daily visits. And while the overwhelming majority of content on these video sites is, to be generous, mediocre, the sheer number of visitors means that the good stuff -- the important stuff -- soon bubbles to the surface. The traditional news networks are no longer the gatekeepers for video documentation of the world.

Imagine: a kid with a cheap cameraphone could take a picture or video that changes the practices of a business, the course of an election, or the policies of a nation. But the kid wouldn't be doing it alone: it requires the knowing, active cooperation of masses of digital allies.

The notion of collaborative efforts to raise awareness and offer ideas isn't limited to the conventional media of text and video; the explosion of 3D, immersive virtual worlds, collectively called the "metaverse" by insiders, offers the opportunity to share not just ideas, but experiences. Some try to replicate the real world to the smallest detail, while others offer utterly unreal, but still compelling, environments.

You may think of these as just games. But 10-15 million people around the world take the time to immerse themselves in virtual worlds, and these settings have played host to political protests in China and policy speeches in Europe (link coming). One US-based virtual world, Second Life, has become an online home for dozens of emerging organizations looking at the intersection of technology and politics.

So, first we have the openness model, which encourages sharing not just tools but the instructions for making, modifying and using them. Second, we have the collaborative information networks including blogs, wikis and citizen journalism, which encourage the use of networks to build on each other's ideas. Both of these are already powerful engines of public participation. But together, they can be revolutionary.

Consider: we're moving into a world where the public, through the use of collaborative tools and open models, can be as effective -- sometimes even more effective -- than traditional top-down authorities in gathering and analyzing useful information. The originator of the term "open source" once said that, with enough eyes, all bugs -- all problems -- are shallow. That is, with enough people working together on a project, details that individuals or small teams could easily miss are instead easily spotted. What the Internet has done, and continues to do at an ever-increasing pace, is make that collaboration simpler, faster, and far more wide-ranging.

There's Open Source Intelligence, the name for open collaborative efforts to follow global threats, taking advantage of commercial satellite images, digital maps, non-classified information sources, and the ability of software to collect it all...

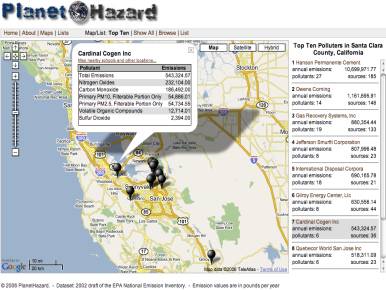

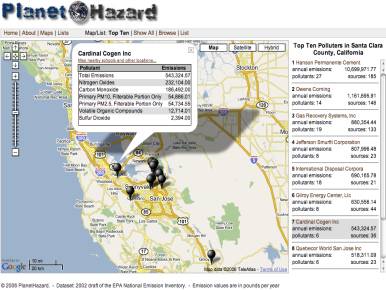

...There are projects to monitor local environmental hazards, again combining multiple information sources into a single easily-understood presentation...

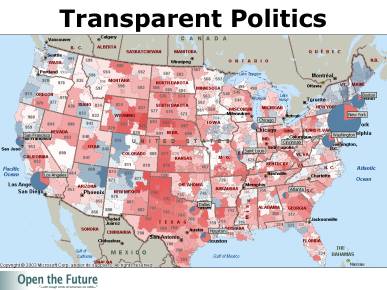

...There are projects to spot patterns in urban crime...

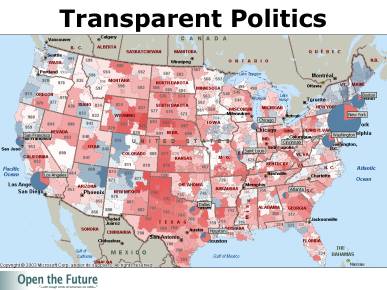

...and patterns in national politics. This site is FundRace.com, which mapped contributions in the 2004 presidential campaign in the US, using data from the US Federal Election Commission. Every contribution over $200 was identified by contributor, and the results plotted geographically, uncovering patterns that would have been hard to spot just by looking at lists of numbers and addresses. FundRace offered its hundreds of thousands of users a way to track the minutiae of campaign money, providing far greater visibility into the political process than US citizens had yet seen.

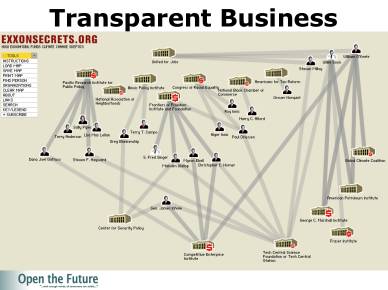

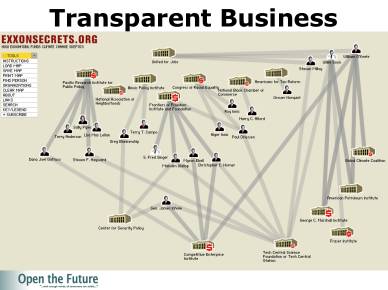

Such practices aren't limited to government information. Troubling patterns sometimes emerge from the collaborative examination of the details of corporate contributions to non-profit organizations and activist groups. ExxonSecrets shows the funding links between the oil mega-corporation and the various groups disputing global warming.

This drive to follow the actions of those who hold political, economic and social power has come to be called "sousveillance." Where "surveillance" means "watching from above," "sousveillance" means "watching from below." It isn't a new idea, but the active collaboration of hundreds, thousands or even millions of online participants gives it far greater strength.

Author David Brin refers to this as "reciprocal accountability." Sousveillance doesn't make surveillance go away; instead, it tries to hold those in power to their own standards. It's an attempt to answer the old question of "who watches the watchmen?" It turns out that, increasingly, we all do.

We saw an example of sousveillance in action at the 2004 Republican convention, where citizen media groups videoed police arrests of protestors. The New York police videotaped the arrests as well, but, according to the New York Times, the citizen media recordings proved that the police had edited many of their own videos to make the protestors appear guilty. Up to 90% of the arrests were thrown out.

This was with traditional video cameras. In the next presidential race in the US, the citizen cameras will be digital, and many will be providing live streaming over the web, making it possible for armies of viewers around the world to catch abuses while they happen.

The shift from traditional video to digital video is more than just a jump in technology and a change in gadgets. It's a change in medium, and it has a global impact. The human rights group Witness has, in the past, given video cameras to activists around the world, in order for them to document human rights abuses. These recordings need to be smuggled out, however, placing every participant in that process in danger. This year, Witness opened the Human Rights Video Hub, in collaboration with the weblog Global Voices Online, offering a central location to upload and store digital video from camera phones and the like. Now anyone with a cameraphone is a potential activist for human rights.

This is a profound development.

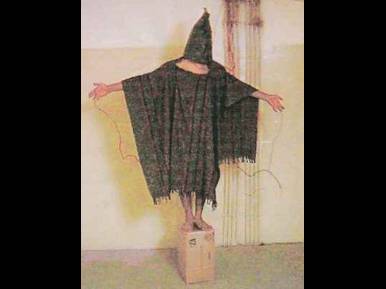

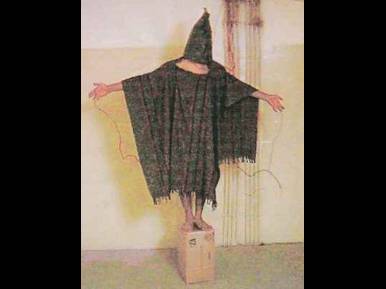

Imagine if this...

...had instead been this, sent out and passed along as fast as the communication networks allow, rather than held in secret until someone let it slip.

Now imagine this visibility being the potential result whenever those in power seek to torture and abuse.

We are moving into a world in which keeping secrets will be harder and harder, and secrets like this will be the hardest of all to keep hidden. Most of us know right from wrong instinctively, but too many of us lack the capacity to do something meaningful when we encounter that which we consider wrong. But we're moving into a world in which nearly all of us will have the necessary means, quite literally in our pockets. This is a remarkable, even transformative, kind of empowerment.

But think back, for a moment, on the examples I began with: collaborative projects like open source science and wikipedia. These are efforts to improve our lives, not simply by highlighting what's wrong, but by building up what's good. Knowledge. Education. The ability of people around the world to improve their own societies and their own lives.

What if, along with the use of these participatory tools to bear witness to what we should be ashamed of, we make a point of using them to celebrate what we should be proud of?

The technologies of participatory culture can be catalysts for progress, expanding our capacity to understand the world and share that understanding with others. Such capabilities are sorely needed now.

We hold the world in our hands. We are rapidly developing the tools to allow us to work together, openly, transparently, responsibly, for our mutual betterment. It's idealistic, but oddly enough, it's a practical idealism. We know these tools work; we're only beginning to understand their power. This is, more and more, an era of remarkable possibility -- and we all have a role to play.

I will be heading to Washington, DC, in a couple of weeks, ostensibly to take part in a short workshop for the Institute for the Future. I'll be coming in a few days early, however, in order to hit a few of the sights (and to spend some time with a good friend). I'll be arriving late on Saturday, December 2nd, and will have free time available for most of Sunday and Monday.

I will be heading to Washington, DC, in a couple of weeks, ostensibly to take part in a short workshop for the Institute for the Future. I'll be coming in a few days early, however, in order to hit a few of the sights (and to spend some time with a good friend). I'll be arriving late on Saturday, December 2nd, and will have free time available for most of Sunday and Monday. It's a holiday week here in the US, and my posting will be a bit more sporadic than usual. Happy Thanksgiving, US readers...

It's a holiday week here in the US, and my posting will be a bit more sporadic than usual. Happy Thanksgiving, US readers...

Well, that didn't take long.

Well, that didn't take long. Lots of good observations in the comments to my post from a few days ago,

Lots of good observations in the comments to my post from a few days ago,

I've had my

I've had my

Okay, giddiness over, back to business.

Okay, giddiness over, back to business. Well, my contributor's copy of the WorldChanging book --

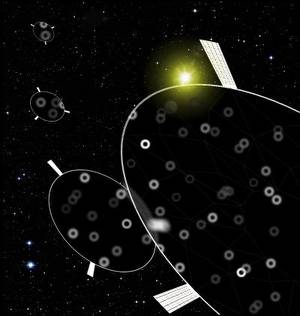

Well, my contributor's copy of the WorldChanging book --  This has "duh... why did we think of this before!" written all over it: a "redundant array of inexpensive disks" to cool the Earth.

This has "duh... why did we think of this before!" written all over it: a "redundant array of inexpensive disks" to cool the Earth. When American voters go to the polls next Tuesday, nearly 40% will encounter a so-called Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) voting machine, usually referred to as a touch-screen voting machine, and another 40% will encounter optical scan voting machines. The security risks involved in the current model of electronic voting are so abundant and so varied that it's almost too big of a problem to consider, but Jon "Hannibal" Stokes at Ars Technica has produced a

When American voters go to the polls next Tuesday, nearly 40% will encounter a so-called Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) voting machine, usually referred to as a touch-screen voting machine, and another 40% will encounter optical scan voting machines. The security risks involved in the current model of electronic voting are so abundant and so varied that it's almost too big of a problem to consider, but Jon "Hannibal" Stokes at Ars Technica has produced a