Abundance, Scarcity and Beta-Testing Tomorrow

I often cite molecular nanotechnology as a transformative technology because of its significant potential implications, especially societal implications. In principle, given inputs of relatively common raw materials (including materials recycled from objects no longer in use), a full-fledged nanofabrication device would be able to build an array of goods limited more by design availability than by system capacity, from clothing to calculators to combat rifles (and, of course, copies of itself). Even if this is just a subset of the products that people normally buy, such a device would still wreak havoc upon traditional economic models. Different cultures will respond in different ways, of course, but a larger question remains. Economics, after all, is traditionally conceived as the study of exchanges under conditions of scarcity. If scarcity no longer applies, how can we have functional markets?

I often cite molecular nanotechnology as a transformative technology because of its significant potential implications, especially societal implications. In principle, given inputs of relatively common raw materials (including materials recycled from objects no longer in use), a full-fledged nanofabrication device would be able to build an array of goods limited more by design availability than by system capacity, from clothing to calculators to combat rifles (and, of course, copies of itself). Even if this is just a subset of the products that people normally buy, such a device would still wreak havoc upon traditional economic models. Different cultures will respond in different ways, of course, but a larger question remains. Economics, after all, is traditionally conceived as the study of exchanges under conditions of scarcity. If scarcity no longer applies, how can we have functional markets?

This is not an idle question. Although molecular nanofabricators safely remain vaporware, few specialists in the field would be surprised to see a working prototype within a couple of decades (and, if Chris Phoenix and Mike Treder are right, an abundance of extremely fast, powerful and complete versions a very short time afterwards). That is to say, if you believe that you have a reasonable chance of making it to, say, 2025, you will likely see how the question of markets under conditions of abundance turns out.

If we're clever, though, we might not have to wait.

Fabrication Nation

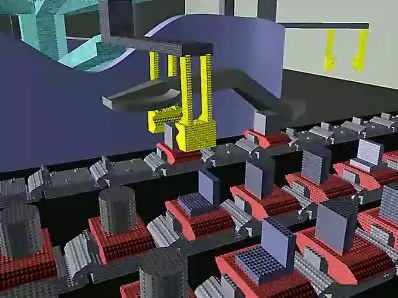

As ideas about molecular nanotechnology evolved over the last couple of decades, proposals for how the technology could work have become less fanciful and much more practical. Eric Drexler's original Engines of Creation concept involved free-floating replicating nanoassemblers, pulling carbon out of the atmosphere to making objects quite literally out of thin air. More recently, the nanoassembly technology moved from hanging around in a so-called "utility cloud" to being boxed up in a desktop device: the nanofactory.

As ideas about molecular nanotechnology evolved over the last couple of decades, proposals for how the technology could work have become less fanciful and much more practical. Eric Drexler's original Engines of Creation concept involved free-floating replicating nanoassemblers, pulling carbon out of the atmosphere to making objects quite literally out of thin air. More recently, the nanoassembly technology moved from hanging around in a so-called "utility cloud" to being boxed up in a desktop device: the nanofactory.

On the surface, the idea of a desktop object printer sounds interesting but not particularly revolutionary. Being able to print out a part or a toy wouldn't make traditional retail chains go away. Most of us have perfectly decent ink jet and laser printers, but we still buy books -- why would it be any different with nanofactories?

The difference is initially subtle, but important: if you print out a book at home, what you get is a big stack of letter-size or A4 paper, not a bound book; if you print out a blender (as a random example) from a nanofactory, what you get is a blender, identical in function and design to one you would have previously purchased in a store. A better analogy for a nanofabber is a CD burner. The CD you burn of a collection of music is identical in use and interaction to a store-bought CD. Anyone laying odds on the music industry surviving in more-or-less its present form through 2016? Now imagine that kind of economic impact hitting not just one industry, no matter how large, but dozens or hundreds, all at the same time.

The notion of nanofabrication is a bit mind-boggling, so to be clear, these aren't "replicators" from Star Trek -- they don't *poof* objects into existence. As this video shows nicely, they will assemble things using raw materials, starting initially at the molecular level and moving up in scale. Given the right combination of base matter, good design, and time, a molecular nanofactory could put together just about any kind of physical good (as long as it doesn't need water, which is really tricky to deal with -- so no hot tea, earl grey or otherwise).

You'd still need raw materials (although with good designs that minimize the use of exotic components and effective product recycling, most useful materials won't be hard to come by), you'd still need energy (although with sufficiently efficient solar and wind power units -- readily built with nanofactories, of course -- energy could be effectively free), and you'd still need designs (although this is exactly the kind of environment in which Free/Open Source would likely thrive). And, of course, you'd need a nanofactory.

Let's call it the StuffStation®.

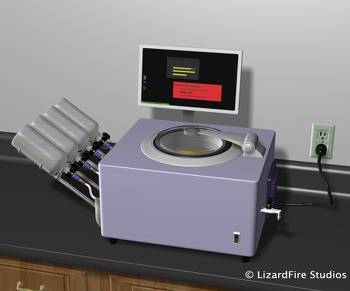

What would a StuffStation® system look like? The home StuffStation® printer would likely be big enough to make a reasonable-sized object, like a laptop or a dress coat, but probably not much bigger; you wouldn't be likely to print out your (electric) car with it, but you'd be able to print any necessary replacement parts. Let's say it's as big as a typical home dishwasher. At one end you have your vat of RawStuff®, either delivered from a supplier (vendor? perhaps) or processed from trash and used gear tossed into your UnStuffStation® mass disassembler, which sits nearby. Since molecular assembly would be extremely material efficient, your vat of RawStuff® will last a good long while.

The unit would have some way for you to tell it what to print, either using a built-in computer interface or a hook-up to whatever home networking system is commonplace by 2025. This would also allow you to load in new designs, either purchased from a developer or acquired from a free design site ("StuffForge.org?"). Just like a typical home computer today, the StuffStation® would likely come with some commonly-used software, but you would need to look for (or write) new programs for additional functions.

Finally, there would be the output. Carrying through the dishwasher analogy, I'd imagine this to be a large door that unlocks when the object is complete and the scaffolding and leftover Stuff® have been recycled. When you hear the "ding," your new gadget/toy/utensil/appliance/outfit/robot pet/weapon is ready.

Of course, there's no reason why you wouldn't be able to have a desktop nanofactory for printing out smaller goods, too -- StuffStation Lite®!

Isn't This Just Like...

Isn't This Just Like...

If we're to imagine what a world in which physical good could be printed out this easily would be like, we might start by comparing the concept to present-day analogies.

Online information offers just such a comparison. There's little scarcity of information online; search engines like Google and Yahoo! contain well over 20 billion entries, and the blogosphere reportedly grows by 175,000 new blogs every day. This abundance has led to the near-collapse of some traditional economic models (e.g., traditional classified ads) and an explosion of new ones (e.g., Craigslist, eBay). Arguably the most abundant form of online traffic is spam, however, and the abundance of malicious hackers/bored pranksters/eager skr1ptk1dd13s necessitates constant vigilance on the part of site owners, service providers and software developers. The easy duplication of digital content has led to epic battles between intellectual property owners and, well, anyone who wants to be able to transfer a song from CD to iPod. Digital Rights Management code makes it hard for everyday users to make casual copies, even while software specialists break the DRM with relative ease.

The notion of comparing the upcoming nanoworld with the Wild West era of the Internet is not a new one. As far back as early 2001, people working in the field of 3D printing technologies talked about "Napster fabbing," where designs for printable objects would be shared & swapped as easily as MP3s. This is potentially a nightmare for anyone who would want to be paid for nano-design work.

This line of thinking leads to more questions. What does spam look like in a nanofactory world? How about network hacking? DRM? Free/Open Source? Is the "look and feel" of a physical object copyrightable -- can you be charged with theft of intellectual property by making your own version of (say) an Aeron chair, even if the design used in no way relies on Herman-Miller code?

Would nanofactories remain offline 99% of the time, with designs brought over by thumbdrive instead of ethernet, simply for security reasons?

When you are able to manipulate atoms as easily as you do bits, the rules of the bit world apply.

Playing with Models

Analogies only go so far. What if we had a space where people lived the abundance society?

We work to make money; we use money as a fungible exchange medium for scarce products and services. If products are no longer scarce, does this mean that the only jobs left will be service positions? Are there enough service positions for everyone? Or do people do the services that they find fulfilling, leaving others to lounge around and/or be non-productively creative?

I'm not a regular Burning Man attendee -- the schedule rarely works out -- but I have gone. My first time wandering the playa, visiting the various camps offering gifts of art, services and/or more physical forms of entertainment, I was struck with a realization: this is one model of what a post-nanotech world might look like. Assume your material needs for food, water, shelter and toys were met, and that you no longer needed to work; what might result is a world where creativity, mutuality, and the gift economy ruled... or a world where sex, drugs and sleeping until 2pm ruled. Or, as with Burning Man, both.

I'm not a regular Burning Man attendee -- the schedule rarely works out -- but I have gone. My first time wandering the playa, visiting the various camps offering gifts of art, services and/or more physical forms of entertainment, I was struck with a realization: this is one model of what a post-nanotech world might look like. Assume your material needs for food, water, shelter and toys were met, and that you no longer needed to work; what might result is a world where creativity, mutuality, and the gift economy ruled... or a world where sex, drugs and sleeping until 2pm ruled. Or, as with Burning Man, both.

The classic question about services-only abundance economies is "who picks up the garbage?" Leaving aside for the moment the argument that UnStuffStations® could render the garbage question moot, or that nano-built robots could handle basic services, Burning Man is instructive on this point, as well. After the burn, individual camps pick up and haul off their own garbage, under the motto "leave no trace;" in the post-burn period, after the campers have left, volunteers scour the ground looking for traces that have been left. The National Park Service regularly commends Burning Man for keeping the Black Rock desert so clean.

Perhaps the answer to the garbage question (and, by extension, the question of the performance of otherwise unfulfilling services) is "volunteers with a sense of responsibility."

The problem with this model is that Burning Man is a self-limiting event, which probably helps to explain why everyone can be so generous of their time, goods and (occasionally) bodies. For most attendees, it lasts less than a week; I doubt few would even entertain the idea of trying to extend that week to a month, year, or lifetime. It's just too hard to be perpetually engaged, creative and responsible. We need to keep looking for models.

World of Nanocraft

If you built an alternate world, one in which you could control everything, from the weather to the availability of resources to the laws of physics, would you include scarcity?

Julian Dibbell, in his new book Play Money, notes that the early virtual world creators made it possible for residents to do or make just about anything within the capacity of the system. Such environments could be enormously fun... for a time. Most residents rapidly lost interest.

Julian Dibbell, in his new book Play Money, notes that the early virtual world creators made it possible for residents to do or make just about anything within the capacity of the system. Such environments could be enormously fun... for a time. Most residents rapidly lost interest.

Contrast the total-abundance environment with a virtual world like Second Life or World of Warcraft, where scarcity is a hard-coded feature -- either to provide a revenue stream for the developer (upgrading to a paid SL account to be able to do more) or to provide a competitive challenge for the players (striving to the be the first to acquire the epic Flaming Staff of Infection in order to defeat one's opponents on the battlefield and hear the lamentations of their women). Dibbell describes it thusly:

...in the end, the worlds [people] actually wanted to be in -- badly enough to pay the entrance fee -- were the ones that made the digital necessities almost maddeningly difficult to come by. All else being equal, in other words, the addictive, highly profitable appeal of MMOs [Massively Multiplayer Online games] suggests that people will choose the world that constrains them over the one that sets them free. (Play Money, p. 41)

These observations derive in part from the work of Edward Castranova, who has long been the leading figure in the study of virtual world economics. Castranova noted the need for scarcity in successful virtual worlds, describing it as the "essential variable" in online economies.

Abundance and Scarcity

So in the nanofab future, what would be abundant and what would be scarce?

Broadly speaking, information and non-organic physical objects would be two categories most dominated by abundant content. In time, the physical object category would expand to include organics like food and medicine, but at the outset at least, it's hardware.

Conversely, services could remain an economically "scarce" commodity, with the caveat that a sufficiently advanced robotics technology would make up for some of that. Until nanofabs can print a sandwich, food would remain scarce. Land would definitely remain scarce; even if super-duper nanofab technologies would allow us to "make the desert bloom," wise environmental regulations would still have a say. In any case, people would still want to live near each other, and still want clean and pleasant environments. A beautiful vista would still be more scarce than a suburban wasteland. Time and attention would remain limited, too -- nanofactories could be enormously powerful, but they won't change the laws of physics.

Given Castranova's observations about online societies of abundance, would that be enough? Would scarcity (in the economic sense) of services, food, land, time and attention be sufficient to serve as the 'essential variable' for nanofactory economics? Or would we need some artificial limitation on physical goods, too?

Ironically, the imposition of nano-era digital rights management technology might actually act as an economic stimulus, by serving as a mechanism for artificial scarcity.

What remains unknown is whether the form of scarcity serving as an "essential variable" is broadly consistent, or whether it differs from person to person. It's likely the latter, in my view; as a result, some of us will strive to find ways around the remaining scarcities. What we need is a virtual world (or set of virtual worlds) built specifically to explore this issue. What kinds of economics emerge in a world of material and information abundance, but service, space and time scarcity? How about when DRM (or some other artificial scarcity mechanism) is added? Or open source?

Second Life partisans will undoubtedly pipe up here that SL comes very close to this, but I'm not sure that the artificial scarcity imposed by the game would offer real-world useful answers.

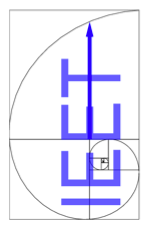

Imagine: a massively-multiplayer environment with plausibly realistic laws of physics; the game initially assigns individual players skills, a bit of money and lodging, and a set of pre-existing economic relationships with other people in the game; at the outset, a small number of players get ahold of virtual StuffStations®, each able to print out more StuffStations® at little cost in energy and raw materials, as well as a cornucopia of other objects. How do the devices propagate? Who uses them to gain rapid power, and who uses them for socially-beneficial (in their view) purposes? How long does it take before a substantial minority has them? A majority? Everyone? What happens when manufacturing jobs are completely unnecessary, and shipping limited to food and people? How many people try to make things for themselves, and make new designs, and how many come to rely on the goodwill of others?

What's the ratio of creativity, mutuality, and the gift economy to sex, drugs and sleeping until 2pm?

Beta-Testing Tomorrow

An online game, even hundreds of them, iterated over and over, will only begin to hint at what a nanofabrication future would be like -- but a hint is better than what we have now: conjecture and (very) broad analogy. I'd like to see this kind of simulation happen at different levels of social organization, as well. Let's see Sim(Nano)City and (Nano)Civilization, or perhaps more pointedly, ultra-modern versions of Risk and Diplomacy played out in a nanofactory era.

The best way to predict the future may be to create it, but that's also the most dangerous way. Once the future has been created, there's no going back; we're stuck with dealing with the results. Simulating the future may not be the best form of prediction, but it's a hell of a lot safer. It would let us try strategies and ideas that would otherwise be far too uncertain or odd to become a real-world approach. It would let us fail safely, pick ourselves up, and try a new path.

The advent of molecular nanofactories may well end up being the biggest social change since urbanization hit the fertile crescent a few millennia back. It might be a good idea to run some tests now to see how that change might turn out. Just a thought.

Comments

This is a really excellent idea. I was thinking of an expansion pack for the Sims; Unfortunately (and ironically), the code is locked up behind an artificial scarcity policy.

Being a veteran burner, I can offer more reasons why BM isn't sustainable. It's still the same consumer society - the consumption is simply offset to before the event. Even ice, juice, and coffee sales are notable exceptions to the no commerce rule. Imagine trying to burn without ice. No way!

Economies do depend on scarcity, and I've always understood that even though some things become abundant, they do so relative to other things that become relatively scarce. Competitive economies will always exist so long as scarcities exist. Molecular manufacturing doesn't make everything abundant at once.

Unfortunately, too many elites respond to sudden abundance by trying to impose scarcity where there is none, so that they can enclose the commons into private property which they can then exclude others from.

The main issue with nanofacs isn't copyright, although copyright will certainly apply to product designs. Instead, patents are the main roadblock to real abundance and social justice in the MM era. In a way, the open source ethos is already paving the way to ensure bad patents get annulled, and really useful things are recorded, published, and (critically) searchable as prior art. In many ways, I consider the copyright wars already won; nanofactories (and their macro-scale 3d printer precursors) will reify these conflicts into the realm of patents.

One problem with this new version of the war is that music, movies, and software never killed anybody, but recursive fabricators have the potential to make - well, BOMBS. Add to this that the US manufacturing sector (most of which is invested in Asia notwithstanding) dwarfs Hollywood in terms of money to be thrown into lobbying, and you have a recipe for some pretty forceful and draconian restrictions on nanofacs.

Regardless, if the DRM that gets built into nanofacs is as effective as what we get in iTunes (where Apple ships it broken, allowing you to burn & rerips mp3s from cds), we're not only in for bad laws, but bomb-toting anybodies, as well.

I can't believe after all this demonstrable failures in DRM, people are still seriously considering applying it to something that's genuinely dangerous. What we need is to design systems that are genuinely incapable of producing dangerous products - not trying to restrict existing systems that already can.

http://n8o.r30.net/doku.php/blog:drmisbadsecurity

As to Second Life, I lost interest in it because it IMPOSES scarcity. I was excited when the GNU/Linux client came out, then realized that all the creative stuff I wanted to do required land locked up behind a paywall, creating a miniature aristocracy - just like physical life. So much for that idea.

http://n8o.r30.net/doku.php/blog:secondlifeforgnulinux

I think you should notice an important qualification in your "essential" ingredient. of scarcity. What's being observed isn't so much that virtual worlds need scarce elements in order to be successful, but that they need scarcity in order to //get people to pay//. In other words, in order to function in the larger scarcity economy, you need a scarcity economy in miniature in the virtual world itself.

Speaking for myself, I just don't get it. I come to virtual worlds to get AWAY from the scarcity problems of the real world. "Grinding" in WoW is bad enough for free - enough to keep me away from it - but for money? You've got to be kidding.

I guess I'm weird that way.

Posted by: Nato Welch | September 12, 2006 4:45 PM

Apparently you are. :)

The relationship between scarcity and activity is interesting. When you say that the games need scarcity in order to get people to pay, you're actually agreeing with the point that scarcity -- artificially imposed or otherwise -- acts as a stimulus to activity. Castranova (and other researchers, both academic and industry) have found pretty convincingly that virtual worlds without scarcity tend to have pretty significant falloff of activity: people just stop showing up.

The grinding in WoW is actually orders of magnitude less tedious than the grinding in (say) EverQuest, but that's neither here nor there.

I hope you didn't think that I was *advocating* the use of DRM as a way of imposing artificial scarcity. I agree with you 100% that DRM is broken and dangerous; it is, however, popular, and I would imagine that there will be attempts to employ it.

I know that copyright and patents cover different things, but I've fallen into the habit of thinking of bit-based intellectual property issues as being copyright, and since atmos follow bits in this world...

thanks for the thoughtful reply

Posted by: Jamais Cascio | September 12, 2006 5:12 PM

Great post, wow. It's probably longer than a blog post should be, and perhaps should've been a detached webpage or essay... but hey, it's your blog!

How come your buddies at Worldchanging seem not to grasp the MNT revolution?

http://nano-catalog.com/

http://www.acceleratingfuture.com/michael/works/nanotechpolicy.htm

I doubt we'll pick up our own garbage like at Burning Man. We'll leave it around, which is what happens 99.9% of the time.

One time in Secondlife, I got ahold of an autobuilder script that let me create 100 blocks/minute. I went up to about 1000m and started making gigantic spheres, then removing their gravity and watching them fall. Months later, I was getting email notices about "an object has been returned to you" and nasty messages about picking up my shit. All it takes is one bored hacker, and you have nanogarbage EVERYWHERE.

Food will not be scarce because we can build thousands of mile-long greenhouses within the first few weeks of nanofactory accessibility. Land will not be scarce because we can build water-filled structures and airships to go anywhere. Environmental regulations will barely prevent 1% of the colonization explosion. See my latest blog entry for more on this.

There will be no 'suburban wasteland' because we'll be able to pump kilotons of water and exotic seeds to whatever coordinates we desire.

Secondlife is probably the best model of a post-nanotech world available to us now.

Posted by: Michael Anissimov | September 13, 2006 3:13 AM

Michael, I'm with you about this being too long. But as I was writing it, I found that there was more and more to say...

I like garbage that identifies its creator. If you had to go clean that up yourself -- rather than wait for others to mail it to you -- you might think twice about that particular expression of boredom.

This is probably worth an overly-long blog entry of its own, but in short: I'm much less sanguine about the ability of nanofactories to enable a "we can do anything" society. Not because we couldn't, per se, but because actions have repercussions, and getting the intended results generally will be a whole lot more difficult than simply putting up a new structure. Making things for (essentially) free is only one part of the equation, not the final answer.

(I'd go into more detail, but I'm already running late this morning.)

Oh, and: by suburban wasteland, I was being mildly metaphorical. I didn't mean lack of access to water and plants. I meant miles upon miles of tract homes.

Posted by: Jamais Cascio | September 13, 2006 9:29 AM

Ah, damn it. I've been reading Castranova's book 'Synthetic Worlds', and my F'mic essay this week is going to be about that sort of thing, though a rather different angle from this. And now everyone's going to think I nicked the theme from you... ;)

Posted by: Armchair Anarchist | September 13, 2006 1:20 PM

Jamais, Wow! Great piece!

I've blogged it on our Responsible Nanotechnology blog.

One quibble: I think a washing-machine-sized StuffStation would be more than big enough to print a car--probably even a personal airplane. Remember that products can inflate or unfold after manufacture. The biggest/heaviest part might be the energy storage, depending on the technology used.

Oh, and the "UnStuffStation" will probably resemble an incinerator with a really good filter on the exhaust, not a molecular-level disassembler. (This is only important because a nanoscale "universal disassembler" is a common, and wrong, idea that leads to other overly-scary ideas like easy-to-build grey goo.

I hate to even mention these few minor quibbles, because this is an EXCELLENT article. Made me think. Lots of good suggestions and ideas.

Thanks!

Chris

Posted by: Chris Phoenix | September 13, 2006 8:48 PM

Thank you very much, Chris.

An incinerator just seems so... non-elegant. Molecular disassembly may not be the right path, but it seems to me that an underlying design model that relied on cradle-to-cradle-type techniques (e.g., "design for disassembly," focus on easily-recycled materials, and such) would enable an "UnStuff" system that relied as much on mechanical disassembly as chemical.

Posted by: Jamais Cascio | September 13, 2006 10:45 PM

As long time studier of things nano, I am beginning to wonder if nanofactories will be as revolutionary as all that. Maybe we, as a globaly society, will have enough time to get used to the ideas the nanofactory represents when they appear to us in other, easier to implement and nearer to reality, forms.

Digital copying of content already is forcing us to reform and think seriously about public domain, intellectual property laws and compensation for creativity. FOSS has been making waves for more than ten years now.

Automation is already eroding the drugery jobs in the service sector. How are we going to employ our teenagers when the fast food joints and supermarkets are essentially giant vending machines? People are already worried about this.

The fabricators spoken of by Neil Gershenfeld and MIT's Center for Bits and Atoms are already being implemented in the real world. This is probably where it will start. This where it will become most obvious even before the nanofactory itself is actually built.

Maybe this is a good thing. Provided we can make good decisions on the issues that already confront us with FOSS, IP Law, automation and desktop fab-labs, when the nanofactories finally arrive society will be pretty well prepared for it.

The key questions are how do we compensate creativity and how do we provide incentives for people to use their time productively. If we can crack those two, the rest will be easier. I think.

Posted by: Pace Arko | September 14, 2006 12:01 AM

I'll tell you what'll be scarce when MM rolls around: jobs

Posted by: Nato Welch | September 14, 2006 3:30 PM

Okay, that's a not-unreasonable conclusion. Why do you think this will be the case, Nato?

Posted by: Jamais Cascio | September 14, 2006 3:35 PM

If one can make perfect $20 bills I think I could like this technology a lot ;->

Posted by: Purple Avenger | September 16, 2006 9:21 AM

Still open to hearing your further thoughts on this Jamais... if we have machines that can make anything, then why won't that eventuality manifest? Just because it "seems" too far-out? Please explain.

Posted by: Michael Anissimov | September 16, 2006 10:30 AM

Sorry, the jobs snipe was just a drive by, at the time.

I'm mostly following arguments made James Hughes and Marshall Brain about the generalized effects of automation, AI/IA, and robotics. MM has a more perhipheral contribution to that, and much will depend on the order in which MM appears relative to mental technologies.

Up to now, the reason technological development hasn't already caused disastrous unemployment is that new markets that threaten old ones have offered workers new opportunities - but the uptake has been limited by the labor supply, and that's been limited by the speed with which workers can afford retraining.

Once synthetic job skills - be they synthetic AI, or some form of neurotechnolgy that extends human capacitie s with commodity computers, things look more interesting, but not terribly different. You can duplicate expertise (AI or IA) easily by adding more computers, but it's likely that computer equipment will remain expensive and scarce for these complex apps.

...At least, until MM rolls around. At that point, the "computronium" explosion comes around, flooding the market with computers, which in turn, flood the supply in many //labor// markets as well.

//FAST//. (unmodified) People won't have time to retrain, because, after a certain point, the modified or synthetics will be learning faster, and, once they learn, an emplyer can simply reproduce that "employee" as many times as he wants - or as many times as he can contract.

"human-level" (or at least job-level) AI/IA + MM (exponential replication of that labor) = labor glut. Different job skills will experience this at different times, but, almost by definition, the pacing is set by research (or by the market leaders), instead of by the pace that //people// can re-adjust to the new labor markets, because the leaders can get there first, and take up ALL the jobs the market can bear to create.

Posted by: Nato Welch | September 17, 2006 8:39 PM

Interesting blog and follow on comments – the “economics” of abundance has been a major area of interest of mine for some time and a obvious follow on to the whole MM emergences.

It seems we are constrained in supposed solutions as much by our inability to get conceptually beyond the idea of “something for (effectively) nothing” and “no work” given work has been a core component of the social fabric. Labour, has been a constant in human cultures since pre-history, we do not have the comparison of a social format that does not require “labour” of at least some of the members to maintain. Regardless that all cultures have had some proportion of “idle rich” (i.e. Paris Hilton etc) there has remained those who provide the required often unpleasant “labour” to maintain a society.

So what are the social consequences of NO labour?? Well for a start it’s a silly idea what is more likely is the rise of greater choice of labour (intellectual, spiritual, manual, collective etc, think hobby farms, cottage industry etc). Socially it seems since the rise of the middle class over the last 250 years and industrialisation increasing leisure time we (oddly enough) have found lots to do with out lives once the mechanics of life are accounted for. The emergence of options for labour that does not result in maintaining ones life will I suspect be a great enabler, it may result in a radically different sort of social fabric and certainly provide the opportunity for many people to live as they choose, rather than as they need to.

One last point, games and sim worlds which rely on economic drivers and remain popular I think is because they require a simplistic, uncomplicated set of core challenges easily understood by the vast majority of players – Example is EVE-Online (currently up to 30,000 simultaneous players online) which is fundamentally based on the “getting money, buying bigger spaceships and control your territory” model with choices on how you do that (mining, manufacturing, piracy etc). They remain popular not because they are different or offer intellectual challenge but because they are familiar and let you blow things up without consequences.

Posted by: Nick R | September 19, 2006 6:40 PM

Good initial post, James, and good discussion so far. Apologies for being a johnny-come-lately to this topic & its posts, but I'm almost dumb-struck by a lack of attention to (1) catallactics (or *exchange* economics) and (2)Kelsonian theory.

A society awash in both nanotech and human+ robotics (both of which are in the offing within the next 20 yrs +/- 5) will not need much in the way of markets or *exchange* for the basics (and even most luxuries). See Jim "Cyber" Lewis' clever discussion on "Robotopia" at http://www.cyberlewis.com/graphic/posthuman/topia/Robotopia.htm . If all one has to "interact" with or "exchange" with is a cybernated system of one sort or another to get most if not all of the goodies of life, then there will tend to be VERY little ***economic*** exchange (as distinguished from more general **interaction** of some sort(s) or another(s)), if only because, ex hypothesi, such exchange would be beyond redundant/superlous, it would be logically ruled-out. Our projective investigations as to what a "nanotech" and/or "robotech" world will "BE" like, *must* take this into accout, because modern economies---and, concomitantly, modern economic theory---is based on **exchange**, on *catallactic* ("exchange") institutions & processes.

2. Louis Kelso has already pioneered an innovative way to make sure that every person, every household has a sufficiency of wealth-producing, income-producing **capital**, which will (fairly soon-on, now) consistent of (smart) robotic and nanotech artifacts. When these latter render human labor redundant, there can still be abundant (!) room, for the first time in history, for all humans to engage in **leisure-work**, the work of self-actualization and civilization. I heartily recommend to all discussants here that you search on "Louis Kelso" or "Kelso Economics" on Google or Dogpile, and there you'll find abundant references for further edification.

And Nato Welch makes an EXCELLENT point, in passing: We will soon-on have "JOB-level" robotics and cybernated systems, even before we have human(-&-beyond) robotics/A(G)I. With proper engineering (itself robotic/AI assistable), robotic systems need not be especially "human-level" to nonetheless ***either*** AUTOMATE ***or*** **OBVIATE** many current "jobs". Most jobs (and even occupations and "professions") can eventually---and SHOULD--- go the way of MOAT engineers/builders. Bring on the Robots!!

Indeed, grok this excerpt from Lewis' *Robotopia* riff:

Robotopia will be operational:

1. When individual robots are intelligent enough to do assigned jobs and mutually communicate needs and performance data without human assistance, and

2. When robots operating in concert can replicate either themselves or design, make and program all the other needed types of robots directly from raw materials without human assistance, and

3. When robots can have access to endless supplies of electrical energy by controlling at least one major energy source, such as coal or oil and a few power generation plants, and

4. When robots can evaluate production facilities, assess and project product demands, then control, adjust and/or build those facilities themselves in advance of need and without human assistance.

I should greatly appreciate your feedback, dear colleagues!

Thanks for the privilege and honor of contributing to this post...

Posted by: MCP2012 | December 18, 2006 8:35 PM