(In case it's not clear...)

(You actually want to do the opposite of all of those. Seriously.)

(You actually want to do the opposite of all of those. Seriously.)

1. One change at a time. Too many changes are confusing, so the only approach is to take a single point of difference from today to its logical conclusion.

1. One change at a time. Too many changes are confusing, so the only approach is to take a single point of difference from today to its logical conclusion.

2. The only changes that matter are technological changes. And by technology, you should mean consumer information technology.

3. Stuff works. Every new invention performs exactly as intended, with no opportunities for misuse.

4. People just want to talk about which brands they use and how stuff works. Be sure that your scenario narrative includes lots of these kinds of conversations.

5. The behavior of people, companies, and governments in your scenarios don't have to make sense. Incomprehensibility is futuristic!

6. You only need to talk about the economically-dominant social group in your own country, e.g., middle-class white American guys. Other groups and other countries will just emulate them.

7. It's more believable if it's depressing. Dystopian scenarios show you're taking your subject seriously.

8. A scenario is just a morality play. Tell your audience what they should be thinking by showing how everything is better with your desired changes, and how everything is worse without them.

9. It's useful to have a good scenario, a bad scenario, and a middle-of-the-road scenario. People need to know how to pick between them.

10. When in doubt, copy from a science fiction TV show or movie. Those guys always get it right!

(tap tap... this thing on? There's dust and cobwebs all over the place.)

My most recent three Fast Company pieces are all of a set, part of the Futures Thinking series. Mapping the Possibilities (Part One, Part Two) give some practical advice for coming up with differing scenarios as part of a futures thinking project. Writing Scenarios offers up a set of real-world scenarios as examples of different styles.

Part One offers some advice as to how to think about what you're going to do:

Foresight exercises that result in a single future story are rarely as useful as they appear, because we can't predict the future. The goal of futures thinking isn't to make predictions; the goal is to look for surprising implications. By crafting multiple futures (each focused on your core dilemma), you can look at your issues from differing perspectives, and try to dig out what happens when critical drivers collide in various ways.Whatever you come up with, you'll be wrong. The future that does eventually emerge will almost certainly not look like the scenarios you construct. However, it's possible to be wrong in useful ways--good scenarios will trigger minor epiphanies (what more traditional consultants usually call "aha!" moments), giving you clues about what to keep an eye out for that you otherwise would have missed.

Part Two lays out the basics of world-building:

World-building is, in many ways, the mirror-opposite of a good science fiction story. With the latter, the reader only needs to see enough of the world to make the choices and challenges facing the characters comprehensible. The world is a scaffolding upon which the writer tells a story. Clumsy science fiction authors may over-explain the new technologies or behaviors--where they came from, why they're named as they are, etc.--but a good one will give you just enough to understand what's going on, and sometimes a little less than that (trusting that the astute reader can figure it out from the context).Scenarios, conversely, are all about the context. Here, it's the story that's a scaffolding for the scenario--a canvas upon which to show the critical elements of the world you've built. A good scenario doesn't make a good science fiction story--but it's a setting within which a good science fiction story might be told.

And Writing Scenarios looks at the different styles that can be employed to tell a scenario story:

In Scenario-as-Story, the presentation is similar to that of a work of fiction. Named characters operate in a lightweight plot, but in doing so engage in behaviors that display key aspects of the scenario. [...]The advantage of the Scenario-as-Story approach is that fiction is a familiar presentation language for readers, and they can more readily grasp the changes to one's life that emerge from the scenario. A story model lets you describe some of the more nuanced aspects of a scenaric future. The disadvantage is that, generally speaking, scenarios are lousy fiction. Even the best-written scenario stories generally wouldn't pass muster with a fiction editor.

The examples I use are from the project I did with Adaptive Path (for Mozilla) in 2008, looking at the future of the Internet. The full set of scenarios can be downloaded here (PDF).

This week's Fast Company is now up. Futures Thinking: The Basics is an introduction to foresight and futurism, with the goal of making it something that many people can engage in productively.

Long-time futures practitioners may find the method described overly-simple, but my goal wasn't just to present something that could be readily understood by a reader without any futures experience. I also wanted it to be something that the people using the method could easily explain to their peers.

It's a pretty common problem in foresight work -- people engaged in a futures workshop get excited about the project and its implications, but find that they are unable to explain to their colleagues back home what they went through and what it meant. They keep getting caught up in trying to make sense of the process, to explain it in a way that is meaningful to those not in attendance.

The four scenario archetypes I describe are also quite a bit simpler than the "futures archetypes" employed by graduates of the University of Hawaii Futures Studies program. Those four (Growth, Collapse, Discipline, and Transformation), while useful, still require a bit of explanation as to their meaning. Is a slow decline a Collapse? Is Transformation a positive scenario? The advantage of the super-simplified archetypes (listed below) is that they're casual, not jargon, and most people would have roughly parallel interpretations of their meaning.

One technique that's good to start with is to use what some professionals call "futures archetypes"--generic headlines that offer platforms upon which to build more specific stories. Four that can be very easy to use are expectations:The first three are fairly self-explanatory, but the last may be a surprise. The goal with the fourth archetype is to explore possibilities that completely shake things up (a big earthquake, perhaps, or a war, or a revolution in computing power). This doesn't mean fantasy--alien invasions and robot uprisings are probably best left to the movies--but it does mean something outside of your expectations. The phrase I love to use for this is "plausibly surreal."

- The future is what I expect.

- The future is better than I expect.

- The future is worse than I expect.

- The future is weirder than I expect.

Yes, once again I work "plausibly surreal" into the conversation.

I was pinged recently by the UK outfit Forum for the Future, a foresight team specializing in sustainable futures. They wanted to know what I thought would be the key issues the world would be confronting in 2030. "Climate" is the first thing that popped to mind, unsurprisingly, and we talked for a bit about what that might look like. (I also argued for molecular nanotechnology as a likely disruptive element to the world of 2030, and I'll examine what that might mean down the road.)

I was pinged recently by the UK outfit Forum for the Future, a foresight team specializing in sustainable futures. They wanted to know what I thought would be the key issues the world would be confronting in 2030. "Climate" is the first thing that popped to mind, unsurprisingly, and we talked for a bit about what that might look like. (I also argued for molecular nanotechnology as a likely disruptive element to the world of 2030, and I'll examine what that might mean down the road.)

Something I didn't get to go into, but is on my mind these days, is the possible political shake-up coming in part from how we respond to climate disruption. 2030 is a good target point for this issue, since I'm fairly confident that by then we'll have seen some significant changes in how we govern the planet.

This scenario most likely to make this apparent is one in which we embark upon a set of geoengineering-based responses to the climate problem (not as the sole solution, but as a disaster-avoidance measure), probably starting in the early-mid 2010s. These would likely be various forms of thermal management, such as stratospheric sulfate injections or high-altitude seawater sprays, but might also include some form of carbon capture via ocean fertilization, or even something not yet fully described*. Mid-2010s strikes me as a probable starting period, mostly out of a combination of desperation and compromise; geo advocates might see it as already too late, while geo opponents would likely want to have more time to study models.

As a result, by 2030, while various carbon mitigation and emission reduction schemes continue to expand, a good portion of international diplomacy concerns just how to control (and deal with the unintended consequences of) climate engineering technologies. It's not impossible that there will be an outbreak or two of violence over geo management. I wouldn't be surprised if at one point, the world ceases geoengineering, only to find temperatures bouncing back up quickly; geo would then almost certainly be resumed.

This is a challenging world, and not just because of conflicts over control or the potential for unexpected impacts. It's a world in which the two familiar models of power -- "hard" military power and "soft" cultural power -- don't adequately describe the arena of competition. Although geoengineering might have the potential to be used harmfully, it would be insufficiently visible, swift, and controllable to serve as a broadly useful form of force; similarly, the memetic elements of a geoengineering strategy are keenly focused on scientific debates over uncertain results, a form of discourse which tends to be opaque to most citizens.

And the struggles over geoengineering wouldn't be happening in a vacuum. Over the next couple of decades, we'll be dealing with multiple complex global system breakdowns, from the present financial system crisis to peak oil production to the very real possibility of food system collapse. Climate disruption, with or without geoengineering, clearly falls into the category, as well: systems in which neither hard nor soft power work very well. All of these problems demand greater information analysis, long-term thinking, and accountability than traditional forms of power tend to offer.

The era of overlapping system threats is now clearly underway, and geoengineering will be a highlight of that period. New patterns of international behavior will almost certainly have emerged by 2030. My gut sense is that they'll have a strong legalistic component; in particular, one of the major points of debate over geoengineering will be liability for negative consequences. Given the need to deal with these overlapping crises, we might imagine the third form of power (beyond hard and soft power) as a kind of "administrative" power. (There's an intentional echo here of Thomas Barnett's "sysadmin force" concept, but this isn't meant as a direct link.) Although much of what I've been discussing here about administrative power focuses on the actions of states and transnational entities, the same concept could easily be applied to bottom-up groups and movements (just as hard and soft power concepts operate at both ends of the scale).

I know that the notion of administrative power as a parallel to hard & soft power isn't quite right. But there's something there about an alternative model of competition that works directly with complex interconnected global systems. Geoengineering won't be the cause of it -- really, the emergence of administrative power (or whatever you call it) is already underway -- but could well be the action that makes this model of power clearly visible.

And yes, "administrative power" is a boring name.

Today is the "preview" launch for Superstruct, the massively-multiplayer forecasting game. The game goes live on October 6, but there are already people out on the intertubes starting to do very cool stuff. For those of you who use Twitter, I've started a Superstruct in-game feed @cascio2019. All signs are that this is going to be big.

Today is the "preview" launch for Superstruct, the massively-multiplayer forecasting game. The game goes live on October 6, but there are already people out on the intertubes starting to do very cool stuff. For those of you who use Twitter, I've started a Superstruct in-game feed @cascio2019. All signs are that this is going to be big.

Here's the content that went live today.

Video reports on the five superthreats:

And "The Final Threat" -- the overview report from the Global Extinction Awareness System.

The human species has a long history of overcoming tremendous obstacles, often coming out stronger than before. Indeed, some anthropologists argue that human intelligence emerged as the consequence of the last major ice age, a period of enormous environmental stress demanding flexibility, foresight and creativity on the part of the small numbers of early Homo sapiens. Historically, those who have prophesied doom for human civilization have been proven wrong, time and again, by the capacity of our species to both adapt to and transform our conditions.It is in this context that the Global Extinction Awareness System (GEAS) offers its forecast of the likely extinction of humankind within the next quarter-century.

(Yeah, I wrote it. At some point, I need to learn how to write in a mood other than "solemn big picture.")

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASESEPTEMBER 22, 2019

Humans have 23 years to go

Global Extinction Awareness System starts the countdown for Homo sapiens.

PALO ALTO, CA — Based on the results of a year-long supercomputer simulation, the Global Extinction Awareness System (GEAS) has reset the "survival horizon" for Homo sapiens - the human race - from "indefinite" to 23 years.

“The survival horizon identifies the point in time after which a threatened population is expected to experience a catastrophic collapse,” GEAS president Audrey Chen said. “It is the point from which it a species is unlikely to recover. By identifying a survival horizon of 2042, GEAS has given human civilization a definite deadline for making substantive changes to planet and practices.”

According to Chen, the latest GEAS simulation harnessed over 70 petabytes of environmental, economic, and demographic data, and was cross-validated by ten different probabilistic models. The GEAS models revealed a potentially terminal combination of five so-called “super-threats”, which represent a collision of environmental, economic, and social risks. “Each super-threat on its own poses a serious challenge to the world's adaptive capacity,” said GEAS research director Hernandez Garcia. “Acting together, the five super-threats may irreversibly overwhelm our species’ ability to survive.”Garcia said, “Previous GEAS simulations with significantly less data and cross-validation correctly forecasted the most surprising species collapses of the past decade: Sciurus carolinenis and Sciurus vulgaris, for example, and the Anatidae chen. So we have very good reason to believe that these simulation results, while shocking, do accurately represent the rapidly growing threats to the viability of the human species.”

GEAS notified the United Nations prior to making a public announcement. The spokesperson for United Nations Secretary General Vaira Vike-Freiberga released the following statement: "We are grateful for GEAS' work, and we treat their latest forecast with seriousness and profound gravity."

GEAS urges concerned citizens, families, corporations, institutions, and governments to talk to each other and begin making plans to deal with the super-threats.

###

This is a game of survival, and we need you to survive.

Super-threats are massively disrupting global society as we know it. There’s an entire generation of homeless people worldwide, as the number of climate refugees tops 250 million. Entrepreneurial chaos and “the axis of biofuel” wreak havoc in the alternative fuel industry. Carbon quotas plummet as food shortages mount. The existing structures of human civilization—from families and language to corporate society and technological infrastructures—just aren’t enough. We need a new set of superstructures to rise above, to take humans to the next stage.

You can help. Tell us your story. Strategize out loud. Superstruct now.

It's your legacy to the human race.

Want to learn more about the game? Read the Superstruct FAQ.

Get a head start on the game. It’s the summer of 2019. Imagine you’re already there, and tell us a little bit about your future self. Visit the Superstruct announcement at IFTF and tell us in email: Where are you having dinner tonight?

At one point during the multiple days of futures workshops held over the last week, one of my colleagues asked me where I'd learned to facilitate groups. After confirming that he thought I was doing it well, and wanted to learn more (as opposed to wanting to know what to avoid), I told him, and he was a little surprised. You might be, too.

At one point during the multiple days of futures workshops held over the last week, one of my colleagues asked me where I'd learned to facilitate groups. After confirming that he thought I was doing it well, and wanted to learn more (as opposed to wanting to know what to avoid), I told him, and he was a little surprised. You might be, too.

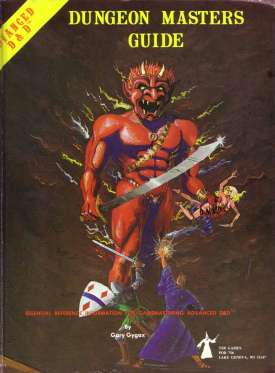

Dungeons & Dragons made me a professional futurist.

Not the subject matter, of course. For the uninitiated, Dungeons & Dragons (hereafter D&D) is kind of like World of Warcraft, with elves and wizards and inappropriately violent people with heavy swords, all in a vaguely medieval setting. The big difference between D&D and WoW is that D&D isn't played on the computer; it requires you and a handful of friends to sit around a table that's covered with sheets of paper, stacks of books with embarrassing covers, and dice. Lots of dice. The other big difference is that D&D emerged in the 1970s, and WoW is totally a ripoff. But I digress.

For the most part, when I played D&D in the 1980s, I served as the "dungeon master" (DM) for the games -- that is, the guy who came up with the stories, managed the games, and threw various hazards at the players. It's not an easy task: the three to five players sitting with you have to run their individual characters, but the DM has to be everything else in the world, and has to make sure that the story moves along fast enough to keep the players interested but carefully enough that the players don't feel railroaded. That role taught me a couple of things that still shape my thinking.

The first is the art of world-building. Although the current version of D&D (as well as the various other surviving non-computer role-playing games) includes a pre-made world in which to play, back in the day we didn't have pre-constructed settings with collections of conflicts and lore and a lengthy backstory, and we liked it. We had to make our own worlds. And if they were to be interesting settings for narrative play, they had to be detailed, internally-consistent, rich with history and key driving forces, and open to players creating novel strategies to deal with seemingly world-shaking threats.

The last part is especially important. The art of world-building isn't the same as the art of story-telling. Stories focus on the characters, and have a strong narrative arc. World-building creates the environment in which the player's characters exist, and offers hooks and platforms upon which the players can, collaboratively, create their own stories.

The parallels here between world-building in D&D and scenario construction for futures work should be obvious. Scenarios have to be detailed, internally-consistent, rich with history and key driving forces, and open to "players" -- that is, the strategists and citizens reading the scenarios -- developing their own strategies of operation. In this case, however, futures scenarios involve the emergence of nanomanufacturing or disruptive climate change rather than the emergence of wizard-kings or disruptive undead hordes.

The second lesson from D&D is the art of invisible guidance. This is where the facilitation skills come into play -- the goal of a DM (facilitator) is to get the players (participants) to follow a particular story-line (strategic argument) and reach a given end-point while making the players (participants) feel as if they'd arrived there naturally. As a facilitator, standing up and telling the participants what they should be understanding and deciding is worse than ineffective, it's counter-productive. Similarly, when a DM gives the players no choice but to accept a quest or follow a path, players often end up pushing back.

Why not just let the players or participants follow where their interests lead? Ideally, that would be wonderful, but both facilitators and dungeon masters have real-world limits on time. If an organization is paying me for seven hours of futures consultation, I had better make sure that what I produce by the end of the day is something that the organization finds worthwhile and appropriate. If a group of friends is going to take a full night out of a busy week to get together and play a game, I had better make sure that they have fun during that session, and feel like they've progressed.

The trick, then, is to make sure that the participants and players move towards an end-point I have in my head without me telling them what that end-point will be. I don't have a checklist for this; for me, it's a style or practice that emerged out of years (a few decades, really) of on-the-job learning. One element that's certain: I always let the participants & players follow tangents for awhile before nudging them back towards the intended narrative. In nearly every case, this provides a better context for the ensuing conversation/game-play.

Obviously, running a D&D game and facilitating a futures workshop have numerous fundamental differences, and I don't want to make more of the comparison than is warranted. But I am at the same time quite convinced that I wouldn't be able to do what I do today without the experience I've had playing these sorts of games. I suspect that, in a variety of important ways, the kinds of thinking and practices encouraged by those games are precisely those that have enormous value today: open-ended strategy; an embrace of the unexpected; and a fundamental reliance on asking "what if?"

The deputy editor of the Economist, Robert Cottrell, thinks he knows what I'm up to. Well, me and the myriad other folks working to analyze what the future could hold, in order to make better choices. In "The future of futurology," Cottrell argues that the only way to have any credibility as a futurist to think small, think short-term, and shut up.

So there you are on the moon, reading The World in 2008 on disposable digital paper and waiting for the videophone to ring. But no rush, because you're going to live for ever-and if you don't, there's a backed-up copy of your brain for downloading to your clone.Yes? No? Well, that's how the 21st century looked to some futurologists 40 or 50 years ago, and they're having a hard time living it down now.

There's a long-standing canard in most conversations about "thinking about the future in a formal way" (a term to avoid the legacies of "futurism," "futurology," and "foresight" -- call it TATFIAFW, or TATF for short). It is rooted in the concept that TATF is a behavior, not a process, and that people who think about the future today do so in exactly the same way as those who did so 50 or 100 or 200 years ago. It's like singing -- some people do it better than others, and there's some training one can do, but people today as a whole aren't any better or worse at singing than people of centuries past. Criticisms of TATF based on past failures or lunacies (pun intended), from this perspective, are equally valid when carried to modern TATF.

If we think of TATF as a process, a skill, or a practice (avoiding the loaded term "social science"), however, it stands to reason that techniques can improve over time. That it's possible to learn from past mistakes. That the changes in our various academic understandings of the world -- greater cross-disciplinarity, greater awareness of systemic processes, greater reliance on peer review -- have influenced the practice of TATF, too. Ultimately, that we can say that what we do when we think about the future today is measurably more useful and insightful than what was done 40 or 50 years ago.

Not for Cottrell. He'd rather that we not worry about what's down the road, and focus only on the immediate future.

You can still get away (as we do) with predicting trends in the world next year, but push the timeline out much further, and you might as well wear a t-shirt saying "crackpot".

I'll keep that in mind next time the Economist prints a story about energy use projections (nearly always going through 2020 or 2030), population projections (2050), or any economic analysis (particularly of climate change) that declares with great certainty the impending financial doom of trying to reduce carbon footprints.

The problem may not be the reach, but the scope. There are fields in which it's acceptable to talk about timelines far greater than 1-2 years. We regularly see mainstream discussions of very long-term trends in energy and finance (e.g., Social Security) that talk about points in the future still decades away. What doesn't seem acceptable -- at least to Cottrell -- is any effort to combine these various narrow projections to look for contradictions or reinforcing systems.

But that's exactly what a futurist -- sorry, TATFist -- does.

It's clear, however, that Cottrell (who actually goes on the speaker circuit as a futurist) has an extremely dated view of what TATF really is all about.

Small wonder that futurology as we knew it 30 or 40 years ago-the heyday of Alvin Toffler's "Future Shock", the most popular work of prophecy since Nostradamus-is all but dead.

Because, as we know, no other form of study or intellectual analysis has changed form or approach in the last 30 or 40 years. Oh, wait.

Economic analysis as we knew it 30 or 40 years ago is all but dead.

Political analysis as we knew it 30 or 40 years ago is all but dead.

Environmental study as we knew it 30 or 40 years ago is all but dead.

...and so forth. In those cases, many of the books from 30-40 years ago are still used in understanding the history of the disciplines, but the same can be said of books like Tofflers in the handful of academic futures studies departments.

The larger point is that professional TATF long ago dropped any pretense of offering predictions or prophecies. Single-point predictions are rarely even broadly correct; of greater value are sets of possibilities, offering insights into what kinds of forces are at work shaping how the present becomes the future. For some professionals, this means scenarios; for others, this means mapping. Regardless of the exact methodology, the purpose is to uncover unexpected potential outcomes, allowing strategists and decision-makers to come to more sophisticated and productive conclusions.

One of Cottrell's pieces of evidence is that you don't see TATFists in the media these days.

There are plenty of them about, but they have stopped being famous. You have probably never heard of them unless you are in their world, or in the business of booking speakers for corporate dinners and retreats.

Or you watch the news (where Paul Saffo shows up all the time), or listen to NPR (where Stewart Brand shows up all the time), or work for the US government (where Peter Schwartz shows up all the time), etc.. But I'll concede Cottrell's larger point: there are no celebrity futurists, and there used to be (at least Alvin Toffler). But back in the 1960s, there were celebrity academics of all kinds. That era's efforts to market celebrity would seem primitive today, and social/cultural elites had more say over what names and faces appeared in the narrow forms of popular media. That the celebrity culture has changed, so that more people are conversant with Paris Hilton than Bob Johansen, is not in and of itself a useful measure.

But Cottrell compounds his errors by claiming that, in actuality, there wasn't much interesting going on in the 1960s, so the West listened to TATFists out of boredom.

We can see now that the golden age of blockbuster futurology in the 1960s and 1970s was caused, not by the onset of profound technological and social change (as its champions claimed), but by the absence of it.

Remind me -- when did the civil rights movement, the women's rights movement, the last great uprising of the IRA, the opening of China, the acceleration of the end of imperialism in Africa, all of that -- when did that happen?

Oh, right, the 1960s and early 1970s. Good thing profound social change was absent, or else things would have been *really* chaotic.

Futurologists extrapolated the most obvious possibilities, with computers and nuclear weapons as their wild cards. The big difference today is that we assume our determining forces to be ones that 99% of us do not understand at all: genetic engineering, nanotechnology, climate change, clashing cultures and seemingly limitless computing power.

Implying that, back in the day, a greater percentage of people understood computers and nuclear weapons. Look at the popular media of the era, and it's damn clear that they didn't know how computers worked. Nuclear weapons are another story, because the ultimate impact of nukes is hard to mistake -- that said, I'd be surprised if Cottrell (or the Cottrell of 1970) could adequately explain how a hydrogen bomb works, what a permissive action link is, or how mutual assured destruction differs from massive retaliation (the two big deterrence models of the era).

When the popular sense of direction is baffled, there is no conventional wisdom for futurologists to appropriate or contradict.

And in this one sentence, Cottrell demonstrates his profound misunderstanding of the purpose of thinking about the future. If you recognize that TATF is more than just trying to spot marketing trends, this moment -- "when the popular sense of direction is baffled" -- is precisely when thinking about future possibilities is the most valuable.

But Cottrell will have none of that. He would much rather we think only about marketing niches.

But the best advice for aspirant futurists these days is: think small. The best what-lies-ahead book of 1982 was "Megatrends", by John Naisbitt, which prophesied the future of humanity. A quarter-century later, its counterpart for 2007 was "Microtrends", by Mark Penn, a public-relations man who doubles as chief strategy adviser to Hillary Clinton's 2008 presidential campaign. [Oh, great -- JC] "Microtrends" looks at the prospects for niche social groups such as left-handers and vegan children. The logical next step would be a book called "Nanotrends", save that the title already belongs to a journal of nano-engineering.

And that is the only reference to an emerging technology with the potential to disrupt existing economic, social and even military models. But there's no sense that it might be a wee bit useful to think through the implications of emerging issues like that; instead, we're told to follow the path of Faith Popcorn, consumer marketing guru of the early 1990s.

The next rule is: think short-term.

And by short-term, he means consumer behavior. Snapshots of the next five minutes, not maps of tomorrow.

A third piece of advice: say you don't know. Uncertainty looks smarter than ever before.

This is one rule that I agree with wholeheartedly. Could Cottrell be on a path of now making sense?

A fourth piece of advice for the budding futurist: get embedded in a particular industry, preferably something to do with computing or national security or global warming. All are fast-growing industries fascinated by uncertainty and with little use for generalists.

No, he's not. Setting aside issues of being biased by being embedded (something journalists learned about recently in Iraq), this is simply more misunderstanding of what we're trying to do. Generalism is the heart of TATF, because that's what makes the practice valuable: being able to see the connections that would otherwise be hard to spot for people embedded in a particular industry.

Cottrell cites climate scientists being unwilling to make projections of possible impacts, and asks how TATFists can think they'd do better. Well, for one, the TATFist is likely to have a better chance of seeing new models for dealing with certain and possible problems. And more likely to see unexpected combinations with non-climate issues. And to provide a context for the climate scientists to imagine how the possible effects might emerge.

A fifth piece of advice: talk less, listen more. Thanks to the internet, every intelligent person can amass the sort of information that used to need travel, networking, research assistants, access to power.

And here's his other rule that I agree with. But then he goes and ruins it.

The most heeded futurists these days are not individuals, but prediction markets, where the informed guesswork of many is consolidated into hard probability.

Because we know that these hard probabilities are in no way providing a false sense of certainty and bias confirmation, and are always accurate.

Honestly, what this all says to me is that this guy really doesn't know much about what he's talking about, and assumes that because he hasn't been following the field, the field hasn't changed.

This matrix served as the core of the presentation I gave at Opportunity Green this past weekend and, in a somewhat different form, at the Behavior, Energy and Climate Change conference the week before.

(I'm also looking at it as the core for a book.)

The four boxes represent a variety of "response" scenarios, each embracing elements of the prevention, mitigation, and remediation approaches to solving the climate crisis. Certain approaches may receive greater emphasis in a given scenario, but all three types of responses can be seen in each world. And while individual readers may find some scenarios more appealing than others, none of these stand out for me as indisputably "bad" response models.

The Drivers

The two critical uncertainties used as scenario axes aren't meant to cover every possible force driving change; rather, they're what I've come to see as issues that are fundamental to how the next few decades play out. It should be noted that the drivers are not particularly "green" in emphasis: this matrix structure can be used to think about different scenarios regarding (e.g.) nanotechnology, military developments, even social networks.

The first driver is Who Makes the Rules?, with end-points of Centralized and Distributed. This driver looks at the locus of authority regarding the subject (in this case, climate responses) -- are outcomes dependent upon choices made by top-down, centralized leadership, or made by uncoordinated, distributed decision-making? Centralized doesn't necessarily mean government; a world where a small number of wealthy individuals or corporations play key roles in shaping results would be just as "centralized" as one of state dominance. Similarly, distributed doesn't necessarily mean collaborative; a world of competing actors with diverse agendas and little ability to exert decisive power is as distributed as one of bottom-up civil society movements.

Although my bias tends towards distributed/collaborative, top-down models are often better-able to respond quickly to rapid developments, and can also offer a more predictable environment for business and organizational planning.

The second driver is How Do We Use Technology?, with end-points of Precautionary and Proactionary. This driver looks not at the pace of technological change (something of a canonical scenario driver), but at our political and social approaches to the deployment of new tools and systems. The "precautionary principle" and "proactionary principle" concepts are related, but not identical: this driver is as interested in why we deploy our technology choices as it is in which technologies we choose. Precautionary scenarios can encompass worlds in which governments, academia and/or NGOs fully examine and evaluate new technologies before use, worlds in which customers increasingly demand technologies for prevention or amelioration of possible adverse events, and worlds in which legal liabilities and insurance requirements force slow and careful deployment of new technologies. Similarly, proactionary scenarios can encompass worlds in which developers can test and deploy any new systems meeting limited health and safety requirements, worlds in which customers (whether top-down or bottom-up) strongly favor improved capabilities over limited footprint, and worlds lacking clear mechanisms (legal, political, economic) for stopping deployment.

My bias here is towards a limited precautionary approach, but the need for rapid response may end up pushing towards a proactionary world.

The Scenarios

The combination of these two drivers give us four distinct worlds.

"Power Green" -- Centralized and Proactionary: a world where government and corporate entities tend to exert most authority, and where new technologies, systems and response models tend to be tried first and evaluated afterwards. This world is most conducive to geoengineering, but is also one in which we might see environmental militarization (i.e., the use of military power to enforce global environmental regulations) and aggressive government environmental controls. "Green Fascism" is one form of this scenario; "Geoengineering 101" from my Earth Day Essay is another.

"Functional Green" -- Centralized and Precautionary: a world in which top-down efforts emphasize regulation and mandates, while the deployment of new technologies emphasizes improving our capacities to limit disastrous results. Energy efficiency dominates here, along with economic and social innovations like tradable emissions quotas and re-imagined urban designs. The future as envisioned by Shellenberger and Nordhaus could be one form of this scenario; the future as envisioned by folks like Bill McDonough or Amory Lovins could be another. Arguably, this is the default scenario for Europe and Japan.

"We Green" -- Distributed and Precautionary: a world in which collaboration and bottom-up efforts prove decisive, and technological deployments emphasize strengthening local communities, enhancing communication, and improving transparency. This is a world of micro-models and open source platforms, "Earth Witness" environmental sousveillance and locavorous diets. Rainwater capture, energy networks, and carbon labeling all show up here. This world (along with a few elements from the "Functional Green" scenario) is the baseline "bright green" future.

"Hyper Green" -- Distributed and Proactionary: a world in which things get weird. Distributed decisions and ad-hoc collaboration dominate, largely in the development and deployment of potentially transformative technologies and models. This world embraces experimentation and iterated design, albeit not universally; this scenario is likely to include communities and nations that see themselves as disenfranchised and angry. Micro-models and open source platforms thrive here, too, but are as likely to be micro-ecosystem engineering and open source nanotechnology as micro-finance and open source architecture. States and large corporations aren't gone, but find it increasingly hard to keep up. One form of this scenario would end with an open source guerilla movement getting its hands on a knowledge-enabled weapon of mass destruction; another form of this scenario is the "Teaching the World to Sing" story from my Earth Day Essay.

The Choice

Which scenario is most likely? It depends a bit on how fast the truly disastrous manifestations of climate change hit. Climate catastrophe happening earlier than currently projected would push towards the more proactionary worlds. It also depends a bit on whether governments and corporate leaders continue to lag community and activist groups in terms of willingness to embrace big changes to fight environmental risks. Centralized responses may end up being too little, too late if wide-spread bottom-up models take root.

Ultimately, which one of these scenarios comes to dominate depends on the choices we make today. We simply can't go on pretending that we don't have to deal with this problem for awhile yet, that "the market" or "the government" or "new technologies" will fix everything in time, that we aren't responsible. The more we abandon our responsibilities, our agency, the more likely it is that the world that emerges will not pay attention to our interests. Acting now is no guarantee that we'll get the world we want -- but not acting is as close as you'll get to a guarantee that we won't.

Opportunity Green arrives on Saturday, presenting an impressive line-up of sustainable business leaders, green bloggers, environmental policy experts, and at least one eco-futurist. I am humbled and honored that they've asked me to present the opening keynote for the event. That talk -- "Green Tomorrows" -- will give me an opportunity to describe the different kinds of futures our environmental choices can produce.

Opportunity Green arrives on Saturday, presenting an impressive line-up of sustainable business leaders, green bloggers, environmental policy experts, and at least one eco-futurist. I am humbled and honored that they've asked me to present the opening keynote for the event. That talk -- "Green Tomorrows" -- will give me an opportunity to describe the different kinds of futures our environmental choices can produce.

The conference takes place in Los Angeles, which may not be at the top of the list of most-sustainable cities. But when Green LA Girl Siel asked me to talk a bit about what could make LA's green future unique, I gave her this reply (which she printed in full in her blog at the LA Times):

Los Angeles is a city built on competing visions of the future.On the surface, LA seems to be the realization of all of the leading environmental risks: the auto-centric culture; the suburban sprawl; the overburdened water table; the celebration of all things consumer, from media to merchandise. There's truth to this caricature, unfortunately. And while these environmental burdens could once be seen as persistent annoyances, they're now nothing less than engines for catastrophe.

At the same time, LA embraces constant reinvention. The immigrants passing through, both from outside the U.S. and -- even more often -- from other American states, churn the culture, the economy and the society of Los Angeles in ways that would be hard to replicate anywhere else. With them come new ideas, and the desire for a space to see the ideas flourish. The media industry is itself founded on the notion of creative destruction, entrepreneurial cycles accelerated a hundred-fold; and while the media companies themselves may sometimes forget this underlying truth, and instead seek the comforts of stagnant incumbency, the thousands upon thousands of creative people working in and supporting the industry live the life of creative destruction every day.

Fortunately, Los Angeles doesn't ignore the environmental challenges it faces, and the number of organizations and companies looking for ways to handle these dilemmas is staggering. The solutions won't be simple, and won't be cheap, but will -- if and when they arise -- be globally transformative. If they can work in Los Angeles they can work nearly anywhere, especially in the explosive cities of the developing world. Lessons (and innovations!) from Los Angeles are far more likely to be applicable in Beijing or Bangalore than would techniques copied from Portland or New York.

The quandary that Los Angeles faces, then, is whether to see the environmental risks as the leading driver for innovation and reinvention, or to allow them to turn the megalopolis into the first big failed city-state of the 21st century.

Let me re-emphasize the (buried) point: Los Angeles, with its sprawling, polycephalous geography, overloaded resources and ecological services, chaotic infrastructure, legendary (if a helluva lot better than when I was a kid living there) pollution, and struggles to get out from under decades of bad planning, has the potential to be a model for developing megacities around the world. Despite its many challenges, Los Angeles has the capacity to be experimental, and to iterate its way to a greener future. In doing so, it will allow the world's megacities to follow in its footsteps.

If LA becomes a reasonably sustainable megalopolis, it's a strong indicator that we'll be able to make it through this global crisis with our civilization intact.

(Image from Blade Runner, set in 2012 Los Angeles, in a most decidedly un-green tomorrow.)

This past weekend, I ran a virtual scenario workshop for the Center for Responsible Nanotechnology. All 15 or so of the attendees participated solely by voice and Internet connection, for nearly eight hours over two days. I had never been a part of a workshop done in this way, and to the best of my knowledge, this may be the first time a scenario exercise has been held using this particular set of tools. All in all, the event seemed to go well, with both a sense of accomplishment in the end and a laundry list of improvements to make for next time. But one thing is absolutely certain: it is entirely possible to run a futures event using distributed technology and still retain participant interest -- and generate useful, novel content, as well.

I'll leave aside the particulars of the scenario ideas themselves right now, as we're still working on them and have not yet made them available to the CRN Task Force members. I'd like to talk a bit about the process itself, and why this may end up being not just a functional alternative to traditional scenario workshops, but potentially a preferred approach.

Approximately 15 people participated in the CRN scenario event, including the two CRN leaders, Mike Treder and Chris Phoenix. I served as facilitator. The attendees represented a reasonably broad variety of disciplines and backgrounds, although all had sufficient interest in and knowledge of molecular manufacturing to be a part of the CRN discussion. Most resided in North America, but one participant attended from New Zealand, and another from Europe; we chose a start time that would be minimally-disruptive to the sleep of the broadest number of participants.

The workshop ran over five forms of media:

Read on to see how we did it.

As noted below, I'm starting to think again about how open source scenario planning might work. First issue to look at is the question of what it means to be open.

As noted below, I'm starting to think again about how open source scenario planning might work. First issue to look at is the question of what it means to be open.

Not all open systems are open in the same way. Although most uses of the term open as a modifier for a system (open source, open society, open bar) reflect open's broad meaning of "freely available for use," the details of how each of these kinds of open systems operate can vary considerably. This becomes a real issue when we encounter -- or create -- new jargon. When we speak of "open biology," for example, what kind of open do we mean? One in which anyone is free to participate? One in which anyone is free to receive the results of research? One in which all research is shared? More abstract variations, such as "open future," only confuse the issue further.

Experts and insiders may grimace at specialized terminology becoming common language, but it usually doesn't help to attempt to narrow the terminology only to its root meaning. In most cases, the democratizing of the term (if you will) happens because the word or phrase expresses something important or useful in a powerful or colorful way. Moreover, the version used in the broader vernacular gains its utility by having a direct link to the original meaning. If we describe something as a "black hole," for example, we probably don't mean that it's literally a body of such immense gravity that nothing can escape, but the popular meaning builds on that core definition.

With that preemptory defense in mind, here's a taxonomy of open systems, derived from the original, technical meanings, but with broader application:

Open Source:

Original version: a category of software in which the underlying programming instructions, or source code, is made available at no cost to interested developers, usually with the stipulation that derivative work should be equally freely shared. (Example: Linux)

OtF version: a system that allows you to reproduce at no cost the underlying design, methods and instructions, as well as the results of the system (if digital), and allows you to build upon either without significant restriction.

Open Access

Original version: a category of scientific publication in which articles are made available at no cost to the reader, who may also duplicate and share the material with others. (Example; PLoS)

OtF version: a system that allows you to reproduce its results or description freely, and to build upon these results without significant restriction.

Open Standard

Original version: a category of technical design made publicly available and implementable, in order to guarantee compatibility across components. (Example: HTML)

OtF version: a system that allows you to build upon its results, including building compatible systems, without significant restriction.

This taxonomy allows for a re-examination of the concept of "open source scenarios" (OSS).

In my original OSS concept, scenario creators would make freely available the scenario model (the key question, potentially the structure of divergent worlds), the scenario narratives (the stories and descriptions of each divergent world), and the scenario drivers (the various uncertainties, driving forces, and catalysts of change identified by the workshop participants). This falls squarely into the "open source" definition above. A number of scenario and foresight professionals responded to the OSS concept with the argument that even among the clients willing to see the scenario narratives published, few would want to open up the list of drivers, as these are most likely to illustrate where an organization sees internal vulnerabilities.

An open access model would be more comfortable, then, as it would omit the scenario "source code" -- the driving forces, uncertainties, and the like -- but still make the results freely available for examination.

The open standard approach would offer up the key questions and, perhaps, the scenario structure, allowing other scenario creators to consider the same basic set of divergences. This is probably the least useful form of open scenario planning, but might have some application as a learning tool.

I was surprised at how much attention this article, one of the last I wrote at WorldChanging, garnered from the foresight/scenario community. Open Source Scenario Planning is clearly an idea with weight, and it's time to start looking again at what it might entail.

As with the other OtF Core pieces, I'm very happy to have the originals at WorldChanging, but it's important to have the material here, as well.

Scenario methodology is a powerful tool for thinking through the implications of strategic choices. Rather than tying the organization to a set "official future," scenarios offer a range of possible outcomes used less as predictions and more as "wind tunnels" for plans. (How would our strategy work in this future? How about if things turn out this way?) We talk about scenarios with some frequency here, and several of us have worked (and continue to work) professionally in the discipline.

With its genealogy reaching back to Cold War think tanks and global oil multinationals, however, scenario planning tends to be primarily a tool for corporate and government planning; few non-profit groups or NGOs, let alone smaller communities, have the resources to assemble useful scenario projects or (more importantly) follow the results of the scenarios through the organization. Scenario planning pioneer Global Business Network has made a real effort to bring the scenario methodology to non-profits (disclosure: I worked at GBN and continue to do occasional projects for them), but we could take the process further: we can create open source scenarios. I don't just mean free or public scenarios; I mean opening up the whole process.

Let's see what this would entail.

Imagine a database of thousands of items all related to understanding how the future could turn out. This database would include narrow concerns and large-scale driving forces alike, would have links to relevant external materials, and would have space for the discussion of and elaboration on the entries. The items in the database would link to scenario documents showing how various forces and changes could combine to produce different possible outcomes. Best of all, the entire construction would be open access, free for the use.

As a result, people around the world could start playing with these scenario elements, re-mixing them in new ways, looking for heretofore unseen connections and surprising combinatorial results. Sharp eyes could seek out and correct underlying problems of logic or fact. Organizations with limited resources and few connections to big thinkers would be able to craft scenario narratives of their own with a planet's worth of ideas at their fingertips.

This is what a world of open source scenario planning might look like.

In software, the difference between "freeware" and "free/open source software (F/OSS)" is whether you can get access to the underlying instruction code for the application, which would then allow you go in and make modifications. With freeware, what you download is what you get; you're welcome to use the tool, but can't change it to fit your own needs, and you'd better hope that the programmer will fix any bugs you find. With F/OSS, conversely, if you have the necessary skills, you can read the program code in order to find ways to improve it for your particular needs, or to fix problems that might crop up. Although most folks will go ahead and use the code as-is, availability of source code means that, with enough interest, the software can be made more robust and useful over time.

Most readers probably understand all of that already, and can see how the model can be applied to similarly code-based processes like biotechnology and fabrication/design. But scenarios are qualitative exercises, not quantitative; scenarios often read like stories, or at least fictional encyclopedia entries, and the explanatory material that usually surrounds them shows how those stories fit with the plans laid out by the particular organization. There's no unique "DNA" or "source code" for scenarios, right?

Not quite.

Now it's true that there's no quantitative, logical process behind scenario creation -- no combination of factors that always leads to a particular scenario result, no matter the author -- but there is still a methodology that can be opened up. The pieces that go into the creation of the scenarios, even the pieces that don't end up in the final narratives, can be valuable in their own right. By making these pieces "free" (as in speech, not beer), the overall capacity of scenario-builders to come up with plausible and powerful outcomes can be improved.

[For this to make real sense, it's important to have a basic understanding of how the scenario process works. Martin Börjesson, in his terrific set of resources about scenarios, describes it this way:

Scenario planning is a method for learning about the future by understanding the nature and impact of the most uncertain and important driving forces affecting our future. It is a group process which encourages knowledge exchange and development of mutual deeper understanding of central issues important to the future of your business. The goal is to craft a number of diverging stories by extrapolating uncertain and heavily influencing driving forces. The stories together with the work getting there has the dual purpose of increasing the knowledge of the business environment and widen both the receiver's and participant's perception of possible future events.

In addition, Katherine Fulton wrote a book on scenario planning specifically for non-profit organizations; GBN has made that book, What If?, available for free download.]

Collections of scenarios from massive corporations and tiny communities alike are easy to find online; what's more difficult to uncover are the lists and discussions of driving forces, critical uncertainties, and the various events and processes that could shape how the future unfolds. These are the scenario planning equivalent of source code, and can be far more useful to groups crafting their own sets of scenarios than the final narratives.

In any scenario planning exercise, participants will spend time early on generating long lists of potential issues and events related to the project's underlying question. These suggestions can be as broad as "global warming" or as narrowly focused as "next version of Windows delayed again." They can, unfortunately, also be quite silly; nearly every scenario brainstorming exercise ends up including at least one reference to whichever science fiction movie is currently popular -- or, at the very least, something from Star Trek. Nonetheless, the list of brainstorming suggestions represents a snapshot of the concerns of the group at that moment in time.

These long lists then get consolidated first by consolidating similar items into meta-categories, setting aside those suggestions that are either too trivial, too unrelated, or too silly to be part of the ensuing discussion. They aren't tossed out completely, however; even the silly items can shape and inspire the ongoing idea generation, and can lead to insights that wouldn't be obvious from the final set of issues.

Traditionally, through some combination of voting and discussion, the list of meta-categories gets narrowed to two key issues that are simultaneously highly important to the question under debate and highly uncertain as to their outcome. They should also be fairly distinct, so that the outcome of one issue doesn't unduly influence the outcome of the other. These two key drivers are crossed to produce four divergent scenaric worlds. The other big drivers remain important, and usually (but not always) get introduced into the resulting scenario narratives.

What starts as dozens and potentially hundreds of issues of varying complexity and relevance gets narrowed first to a smaller set of big issues, then to two key important and uncertain drivers. In most cases, the documentation and explanation surrounding the scenarios includes some discussion of the two key drivers, but little reference to the other issues that the group considered important. The problem is, these other elements often helped shape how the scenario team came to understand the key issues.

An "open source" scenario process, conversely, would retain all of these earlier elements, not as explicit parts of the final narratives, but as a separate "source code" document. Ideally, the long list of issues would include brief explanations and indications of who offered the idea (think of it as "documenting your code"), but even without these additional notes, the content would be useful. Readers could go through the scenarios as before, or could seek out a better understanding of how the scenarios came about by digging through this source material.

As a first pass, simply by publishing online this "source code" alongside organizational scenarios could be enough to allow the development of this open source scenario future. Ultimately, though, there would need to be some way of looking at the various drivers and issues from various sources side-by-side. The Scenario Thinking Wiki looked like a decent start, but it remains a limited and infrequently-maintained effort. The biggest problem is that a wiki requires active effort to keep going. If a similar project managed to develop a following that echoes that of Wikipedia, it would be quite useful; without that collection of devotees, however, the likely result is a slow death.

Instead, an open source scenario database might work better as something more like Technorati, searching for relevant linked and tagged documents to compile into a database. This would still require some active effort on the part of scenario authors, but it would be limited to simply putting the source material up online and adding specific keywords to alert "Scenariorati" that it should include the document.

Most plausibly, however, an open source scenario system could arise through the efforts of a limited number of people, perhaps within a single organization or small collection of organizations, consciously deciding to share their "scenario source code" to help each other out. Ultimately, as a result, all of their scenario exercises would be stronger because of it.

If the open source software mantra is "many eyes make all bugs shallow," perhaps the open source scenario mantra could be "many minds make all futures visible."

It's the number one religion (by proportion of adherents) in the states of Washington and Idaho; it's the number two religion in California, Utah, Massachusetts and Arkansas. In most states, in fact, it ranks as the #2 or #3 belief, and in only a few is it #4 or #5. Nationwide, it ranks #3 overall, just behind Baptist (#2) and Catholic (#1). Yet very few elected officials profess this faith, and a significant plurality of US voters say that they'd never vote for someone who believes this. What is this religion?

It's no religion at all.

Much to the surprise of both the very religious and the entirely irreligious, non-theism consistently shows up as the second or third most popular belief across most states. According to the American Religious Identification Survey (PDF), assembled by the Graduate Center of the City University of New York in 2001, over 14% of US citizens profess themselves to be atheist, agnostic, humanist or secular; this compares to 16% Baptist, and 24.5% Catholic. This map from USA Today shows the breakdown by state (Flash required).

It's worth remembering this in light of recent statements by Sen. Barack Obama about the importance of religion to the Democratic party. Non-believers aren't just a tiny fringe element in American society, and they aren't just found in coastal "blue states." Non-religious people make up a higher percentage of the populations of Idaho, Montana, and Nevada than they do of those of California, Massachusetts or New York. This isn't the narrative we're given by popular culture or media, but it's reality.

I find this useful info for those of us thinking about the future for this reason: the stories we're told about how a society works may not match the reality, and we shouldn't build our models and scenarios based on what we assume to be true.

If scenario creation was the poster-boy for futurism in the mid-1990s, artifact creation looks to play that role for mid-2000s futurism. Combining strategic foresight with what amounts to concept-car design, efforts such as the Institute for the Future's "Artifacts from the Future" and Management Innovation Group's "Tangible Futures" seek to give clients a sense of what tomorrow might hold through the use of physically (or at least visually) instantiated objects. These objects make up in conceptual weight what they may lack in detailed context; holding a fruit carrying a label showing the various pharmacological products added to its DNA is far more arresting than reading a story about big pharma taking over big farmers, let alone a simple listing of this development as a possibility.

If scenario creation was the poster-boy for futurism in the mid-1990s, artifact creation looks to play that role for mid-2000s futurism. Combining strategic foresight with what amounts to concept-car design, efforts such as the Institute for the Future's "Artifacts from the Future" and Management Innovation Group's "Tangible Futures" seek to give clients a sense of what tomorrow might hold through the use of physically (or at least visually) instantiated objects. These objects make up in conceptual weight what they may lack in detailed context; holding a fruit carrying a label showing the various pharmacological products added to its DNA is far more arresting than reading a story about big pharma taking over big farmers, let alone a simple listing of this development as a possibility.

As I've mentioned a couple of times, I'm doing a bit of work with IFTF right now, and I had a chance to handle some of the Artifacts from the Future that Jason Tester and his team devised -- do not underestimate the memetic power of good photo editing skills and a quality color printer.

Business 2.0: "5 Hot Products for the Future"

What makes this method so intriguing is that, often, the objects aren't presented as imaginary possibilities, but as real-world products from a few years hence. The greater the verisimilitude, the greater the sense of dislocation and anxiety. The notion of drug-laced fruit isn't an abstract concept if you can hold what appears to be one in your hand; we're forced to ask what kind of world makes something like this possible -- and just how plausible is it that we could soon find ourselves in that world?

This sort of anticipatory creativity isn't new; product designers have been doing it for decades, as have science fiction writers, game designers, even strategy and innovation consultancies. The game book I wrote a few years ago, Toxic Memes is effectively a big book of future artifacts, albeit mostly social ones (political movements, urban legends and the like). I even managed to come up with something that had a real world manifestation a couple of years later.

The Spacer Tabi

The web has opened up a vast arena for just this sort of playful construction, and it's not too hard to stumble across what appear to be corporate websites for products and services that really shouldn't yet exist. Sometimes, the viewer is let in on the gag with subtle jokes, or even small disclaimers; sometimes, the site presents itself with a completely straight face, leaving even the most skeptical visitor wondering if such things might really be possible -- and if not now, how soon?

Many of these future product websites imagine products and services arising from commonplace genetic engineering. There are numerous reasons for this, both practical and emotional. It's easier to make a plausible modification to a living form than to make a non-living object that looks desirable to consumers without looking like a knock-off of a present-day object. At the same time, we're much more prone to fascination and dismay over biomodification than we are to new pieces of consumer electronics. If the goal is to provoke a visitor response, imaginary bioengineering is the way to go.

GenPets -- mass produced bioengineered pets

Human Upgrades -- biomodifications for human bodies (Warning: some pages are extremely unsafe for the workplace, and potentially startling even for the jaded. I'm serious.)

Provocation is precisely the point of linking conceptual design to strategic foresight. Those of us who spend time crafting imaginary products, services or trends from the future aren't trying to come up with marketable ideas (even if that sometimes happens), we're trying to offer a glimpse at what might be possible, with the goal of pushing the viewer to ask questions about the ways in which the world is changing. Is this the kind of world we'd want? How might we do this differently? How could we make it better? What would have to change before I would use something like this? What would something like this mean for my organization, my family, my life?

Many, perhaps most, future artifacts trigger this provocation by offering up products or services that would be taboo (or, at least, very hard to get past the FDA) today. What we need to see more of are anticipatory designs that provoke us into imagining ways in which the world could be better than it is today. We're starting to see that in vehicle design, from the Aptera hypercar getting 330 mpg to the Daimler-Chrysler "bionic" car echoing the streamlining of the boxfish. Bruce Sterling's Viridian Movement, and his more recent work leading design classes in California, also mix of positive provocation with anticipatory artifacts.

I can't imagine doing a major futurist project now without using some kind of tangible element of the future, even if it's just an article from a magazine of a decade or three hence. These artifacts provide an anchor for the recipients, not in the sense of holding them back, but in the sense of giving them a grounding from which to explore.

In Transmetropolitan, by Warren Ellis, Darick Robertson, and Rodney Ramos, the story's future society has built the Farsight Community, tasked with trying out new technologies for extended periods in order to see what the real-world effects might be. This way, society can make educated choices about widespread adoption of new systems, and can better prepare for risks. We don't have the luxury of a Farsight Community; what we do have are foresight tools, the ability to learn from both successes and mistakes, and -- most importantly -- our imaginations.

The Public Library of Science -- PLoS -- was a pioneer in the field of open access science, making high-quality scientific research results available for free (through a Creative Commons license) to readers around the world. Part of the strength of the PLoS effort was that, aside from the publishing model, the Public Library of Science journals were otherwise standard, rigorous research publications. It turns out, however, that this was just a way of getting its foot in the door of science publication; today, PLoS unveiled PLoS ONE, and has made clear its real agenda -- nothing short of a revolution in science communication.

The Public Library of Science -- PLoS -- was a pioneer in the field of open access science, making high-quality scientific research results available for free (through a Creative Commons license) to readers around the world. Part of the strength of the PLoS effort was that, aside from the publishing model, the Public Library of Science journals were otherwise standard, rigorous research publications. It turns out, however, that this was just a way of getting its foot in the door of science publication; today, PLoS unveiled PLoS ONE, and has made clear its real agenda -- nothing short of a revolution in science communication.

PLoS One will be a multi-discipline online journal offering rapid publication, interactive papers, a selection method that focuses on rigor instead of novelty, and -- most importantly -- an ongoing reader review system that changes the peer review process from a gateway to a conversation. Readers will be able to annotate papers, and to share their commentary and links with other participants. The authors, in turn, will be able to update their work, bringing in additional experimental data and improving the language of their papers for greater reader comprehension (the original version will always remain available, however).

For me, the most exciting aspect of the PLoS ONE project is its inclusiveness:

The boundaries between different scientific fields are becoming increasingly blurred. At the same time, the bulk of the scientific literature is divided into journals covering ever more restrictive disciplines and subdisciplines. In contrast, PLoS ONE will be a venue for all rigorously performed science, making it easier to uncover connections and synergies across the research literature.

The era of the siloed, isolationist scientific disciplines is finally passing. The more that biologists understand physics, that climatologists understand demography, that chemists understand epidemiology (and on and on), the better. We can no longer afford for scientists to be functionally illiterate across disciplines.

Although many of the features of PLoS ONE are familiar mechanisms for readers of blogs, wikis and other web-citizen media, this is pretty radical stuff for the world of scientific publishing. With high-end journals such as Nature or Science, the legitimacy of the research published comes from the high barriers to entry; you don't get into Nature if your work doesn't meet some pretty serious requirements. PLoS ONE will have much less restrictive barriers to publication; the legitimacy of the research will come instead from the community of readers evaluating, testing, challenging and arguing the findings.

It's unclear, as of now, whether readers will have some way to rate the contributions of other readers, building up a Slashdot-style reputation score for participants. I expect that it will. Ideally, participants would evaluate the claims and observations made during the discussion by looking closely at the ideas. Realistically, however, good rhetorical skills and a powerful online personality can cover up gaps of logic or methodology, and new participants should be able to see at a glance who they should watch closely.

PLoS ONE will begin active publication later this year, but interested readers can sign up now for progress reports and submission guidelines.