Those who cannot remember the futurist predictions of the past are condemned to repeat them, usually at conferences. That was the mantra running through my head, at least, during the Metaverse Roadmap Project event last Friday and Saturday. This is not to say that the conference, which included technologists, pundits, academics, journalists, and assorted cross-subject thinkers, wasn't worth the time. It was extremely interesting, in fact, and I'm very happy to have been a part of it. But throughout the discussions, I had this eerie sense of being back in 1996, when the web and the popular Internet began to really show promise -- and technologists, pundits, academics, journalists, and assorted cross-subject thinkers all wanted to be the first to proclaim that the revolution was at hand.

Those who cannot remember the futurist predictions of the past are condemned to repeat them, usually at conferences. That was the mantra running through my head, at least, during the Metaverse Roadmap Project event last Friday and Saturday. This is not to say that the conference, which included technologists, pundits, academics, journalists, and assorted cross-subject thinkers, wasn't worth the time. It was extremely interesting, in fact, and I'm very happy to have been a part of it. But throughout the discussions, I had this eerie sense of being back in 1996, when the web and the popular Internet began to really show promise -- and technologists, pundits, academics, journalists, and assorted cross-subject thinkers all wanted to be the first to proclaim that the revolution was at hand.

The purpose of the Metaverse Roadmap Project (hereafter MVR) was to begin to sketch out the possible evolution of the broad collection of technologies subsumed under the label of the "3D Web." Most of the discussion centered on the 3D virtual world technologies found in games like World of Warcraft and avatar chat environments like Second Life, but the MVR crew quite rightly included people who work on "geospatial web" technologies, too -- location-aware, information-dense systems that layer onto the visible, "physical" world. These are 3D technologies, too, even if they don't use cartoon people and fantasy places.

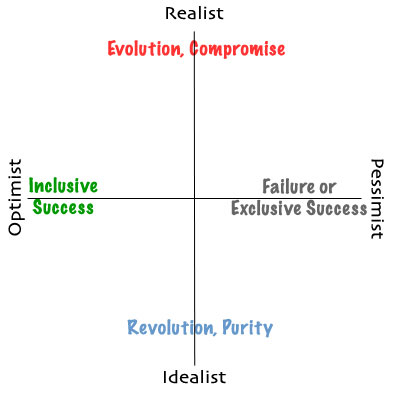

This inclusion of geospatial (or "augmented reality") systems in the metaverse concept allowed the participants to construct a spectrum of scenarios, ranging from the cautiously incremental to the fantastically radical. (I can sum up the latter end of the spectrum in two words: brain implants.) Curiously, the group that fell into the "futurist" affinity group -- me, Esther Dyson, Helen Cheng, Janna Anderson and Randy Moss -- had a strong bias towards the cautious and incremental. I suspect that a great deal of that caution came from having heard technology-drenched proclamations of social revolution before. Fool me once, shame on you; fool me... can't get fooled again. Or something like that.

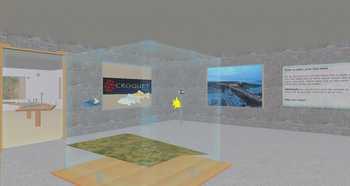

Despite our caution, however, we did manage to catch a glimpse of a truly transformative vision. Open Croquet is an open source, peer-to-peer 3D environment system that everyone who got a chance to see it declared to be shockingly cool. Microsoft's Robert Scoble (who was at MVR for the second day) describes it thusly:

We have just seen a new world. [...]

This is rough, early-adopterish, but once you see this you realize a new kind of computing experience is coming.

...All running P2P. No centralized servers needed. It's remarkable. They showed how you could just "step into" a new virtual world. Just move toward something that looks like a window and you "dive into" that Window and are instantly in a new world. In that new world there would be new people, new things to see.

Sometimes I pinch myself at what I get to be among the first human beings to experience.

Scoble isn't exaggerating -- it was simply that cool. You can download the Open Croquet SDK right now; it runs on Mac, Windows and Linux.

Open Croquet wasn't the only technology demo at MVR, just the flashiest. The variety of tools and ideas kicked around this last weekend in Menlo Park made it very clear that the next decade will see an increasing integration of our virtual existence and our physical lives. In the nearly-certain scenario, this will mean an immersive information environment, accessible wherever and whenever, augmenting and enhancing -- but not replacing -- our day to day experiences. In the more-adventurous version, 3D spaces become a common interface for communication and interaction, putting more of our daily lives into virtual settings, but for largely functional reasons (e.g., working from home).

I'm really hesitant to go as far as many of my colleagues at MVR; I asked There.com's Betsy Book whether the vision she articulated was meant to portray virtual life as augmentation for physical life, or the physical world as augmentation for our virtual worlds. She answered, "Both," and suggested that a large part of the population will see these synthetic worlds as their real homes. But even if the technology is up to it -- likely, but not certain -- it's hard for me to see the cultural transformation required to make this a reality happen in just a decade.

Two aspects of virtual/synthetic/metaversal spaces seemed conspicuous by their relative absence. The first was the distributed awareness technologies of "everyware," "spimes," "things that think" and the like; these aren't directly part of the 3D web, but to the degree that the geospatial and augmented reality components are important, these systems will be seen as part of the package. The second was the fabrication and material production technologies exemplified by 3D printers; as Rebang's Sven Johnson has demonstrated, the connection between the physical and virtual worlds isn't simply a matter of creating digital analogues of material goods -- sometimes, we're going to want physical instantiations of virtual products. To the degree that we shift to just-in-time/local-fabrication economies, the use of synthetic environments to design and test prototype goods could become extremely common.

I may not be ready to buy a homestead in Second Second Life, but it's pretty clear that, at the Metaverse Roadmap event, I got a glimpse of tomorrow's digital world.

Added bonus: I got a chance to have a good, long conversation with WorldChanging board of directors Chair (and Global Voices conductor) Ethan Zuckerman -- and event photographer John Swords managed to get a decent shot of the two of us.

Okay, so I'm the last kid on the block to do this, and it has long been considered kind of silly... but I went ahead and set up Open the Future shirts and mugs (and a couple of other items) over at CafePress.

Okay, so I'm the last kid on the block to do this, and it has long been considered kind of silly... but I went ahead and set up Open the Future shirts and mugs (and a couple of other items) over at CafePress.

David Brin wrote a

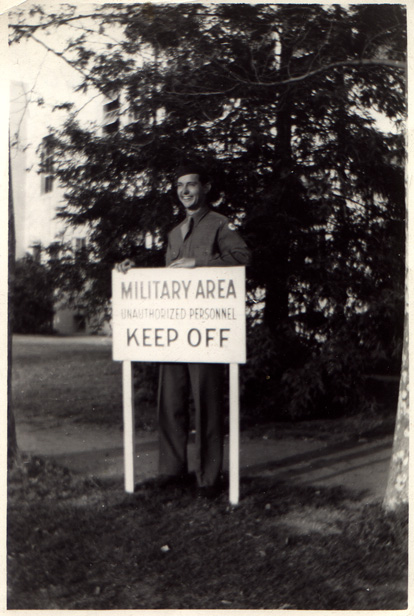

David Brin wrote a  Andrew Jackson Wickline, my grandfather, the man I was named for, died three years ago, shortly before Memorial Day; a veteran of World War II, he was given a military service on Memorial Day itself, 2003.

Andrew Jackson Wickline, my grandfather, the man I was named for, died three years ago, shortly before Memorial Day; a veteran of World War II, he was given a military service on Memorial Day itself, 2003. I look at the people in my grandfather's photos, and wonder: did they know they were remaking the world? Were these simply snapshots to them, vacation photos with an edge, or did they recognize that they were documenting their roles in a monumental political transformation? How would our understanding of the second world war differ if everyone had carried a camera, not just one person out of hundreds, or thousands?

I look at the people in my grandfather's photos, and wonder: did they know they were remaking the world? Were these simply snapshots to them, vacation photos with an edge, or did they recognize that they were documenting their roles in a monumental political transformation? How would our understanding of the second world war differ if everyone had carried a camera, not just one person out of hundreds, or thousands?

The

The

It looks like the first draft version of the

It looks like the first draft version of the

Those who cannot remember the futurist predictions of the past are condemned to repeat them, usually at conferences. That was the mantra running through my head, at least, during the

Those who cannot remember the futurist predictions of the past are condemned to repeat them, usually at conferences. That was the mantra running through my head, at least, during the

The first day of the

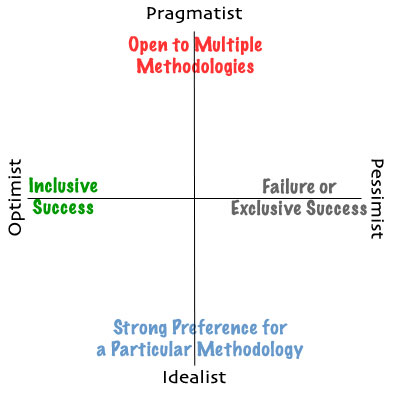

The first day of the  I've been thinking quite a bit lately about how we make long-term decisions. The trite reply of "poorly" is perhaps correct, but only underscores the necessity of coming up with reliable (or, at least, trustable) mechanisms for thinking about the very long tomorrow. Many of the biggest crises likely to face human civilization in the 21st century have important long-term characteristics, and our relative inability to think in both complex and actionable ways about slow processes may be our fundamental problem.

I've been thinking quite a bit lately about how we make long-term decisions. The trite reply of "poorly" is perhaps correct, but only underscores the necessity of coming up with reliable (or, at least, trustable) mechanisms for thinking about the very long tomorrow. Many of the biggest crises likely to face human civilization in the 21st century have important long-term characteristics, and our relative inability to think in both complex and actionable ways about slow processes may be our fundamental problem.