J. Bradford DeLong is a professor of economics at UC Berkeley, and was an economic advisor to President Clinton; Susan Rasky is a senior lecturer in journalism at UC Berkeley, and was an award-winning reporter for the New York Times. Together, they have compiled for the Neiman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard lists of what economists need to know about journalists, and what journalists need to know about economists, in order to result in useful and accurate economic reporting. The lists are straightforward, and if followed would make a world of difference.

This is a remarkably good idea, one with direct application in a number of disciplines that are important for society but prone to obfuscation and confusion in the press: environmental science; bioscience; computer science (pretty much all sciences, in fact); developments on the Internet; and, of particular focus here, futurism and foresight. It's too easy for poorly-informed journalists to skim off unrepresentative (but sound-byte-friendly) examples and concepts, and help to further public confusion instead of help to clear it up.

This isn't because journalists are corrupt or stupid or anything like that: by and large, they're generalists talking about fields that they probably didn't study, under time and financial pressure from editors and publishers who almost certainly know even less. It's a wonder that reportage about science, technology and the future isn't worse than it already is.

Although I think the "12 Things Journalists Need To Know" model has broad application, I'm only going to look at the futurist/foresight area here, and am only going to compile the list for journalists writing about futurists. Fortunately, the instructions for economists about journalists is quite applicable to academics and specialists across disciplines.

Here's my initial draft of 12 -- what would you change?

1. Nobody can predict the future. This should go without saying, but too often, reports about trends or emerging science and technology tell us what will happen instead of what could happen. In fact, most futurists and foresight consultants will avoid making any predictive claims, and you should take them at their word; any futurist who tells you that something is inevitable probably has something to sell.

2. Not everyone is surprised by surprises. The corollary to #1, be on the lookout for people who saw early indicators of surprises before they happened. Just like an "overnight success" worked for years to get there, the vast majority of wildcards and "bolt from the blue" changes have been on someone's foresight radar for quite awhile. When something happens that "nobody expected," look for the people who actually did expect it -- chances are, they'll be able to tell you quite a bit about why and how it took place.

3. Even when it's fast, change feels slow. It's tempting to assume that, because a possible change would make the world a decade from now very different from the world today, that the people ten years hence will feel "shocked" or "overwhelmed." In reality, the people living in our future are living in their own present. That is, they weren't thrust from today to the future in one leap, they lived through the increments and dead-ends and passing surprises. Their present will feel normal to them, just as our present feels normal to us. Be skeptical of claims of imminent future shock.

4. Most trends die out. Just because something is popular or ubiquitous today doesn't mean it will be so in a few years. Be cautious about pronouncements that a given fashion or gadget is here to stay. There's every chance that it will be overtaken by something new all too soon -- and this includes trends and technologies that have had some staying power.

5. The future is usually the present, only moreso. Conversely, don't expect changes to happen quickly and universally. The details will vary, but most of the time, the underlying behaviors and practices will remain consistent. Most people (in the US, at least) watch TV, drive a car, and go to work -- even if the TV is high definition satellite, the car is a hybrid, and work is web programming.

6. There are always options. We may not like the choices we have, but the future is not written in stone. Don't let a futurist get away with solemn pronouncements of doom without pressing for ways to avoid disaster, or get away with enthusiastic claims of nirvana without asking about what might prevent it from happening.

7. Dinosaurs lived for over 200 million years. A favorite pundit cliche is the "dinosaurs vs. mammals" comparison, where dinosaurs are big, lumbering and doomed, while mammals are small, clever and poised for success. In reality, dinosaurs ruled the world for much, much longer than have mammals, and even managed to survive a planetary disaster by evolving into birds. When a futurist uses the dinosaurs/mammals cliche, that's your sign to investigate why the "dinosaur" company/ organization/ institution may have far greater resources and flexibility than you're being led to believe.

8. Gadgets are not futurism.Don't get too enamored of "technology" as the sole driver of change. What's important is how we use technology to engage in other (social, political, cultural, economic) activities. Don't be hypnotized by blinking lights and shiny displays -- ask why people would want it and what they'd do with it.

9. "Sports scores and stock quotes" was 1990s futurist-ese for "I have no idea;" "social networking and tagging" looks to be the 2000s version. Technology developers, industry analysts and foresight consultants rarely want to tell you that they don't know how or why a new invention will be used. As a result, they'll often fall back on claims about utility that are easily understood, familiar to the journalist, and almost certainly wrong.

10. "Technology" is anything invented since you turned 13. What seems weird and confusing will become familiar and obvious, especially to people who grow up with it. This means that, very often, the real utility of a new technology won't emerge for a few years after it's introduced, once people get used to its existence, and it stops being thought of as a "new technology." Those real uses will often surprise -- and sometimes upset -- the creators of the technology.

11. The future belongs to the curious. If you want to find out why a new development is important, don't just ask the people who brought it about; their agenda is to emphasize the benefits and ignore the drawbacks. Don't just ask their competitors; their agenda is the opposite. Always ask the hackers, the people who love to take things apart and figure out how they work, love to figure out better ways of using a system, love to look for how to make new things fit together in unexpected ways.

12. "The future is process, not a destination." -- Bruce Sterling The future is not the end of the story -- people won't reach the "future" and declare victory. Ten years from now has its own ten years out, and so on; people of tomorrow will be looking at their own tomorrows. The picture of the future offered by foresight consultants, scenario planners, and futurists of all stripes should never be a snapshot, but a frame from a movie, with connections to the present and pathways to the days and years to come.

When talking with a futurist, then, don't just ask what could happen. The right question is always "...and what happens then?"

Light blogging week (of course, the week when I get a

Light blogging week (of course, the week when I get a  Last week, at a

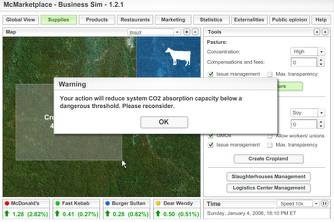

Last week, at a  • Turning Greenhouse Gases into Greenhouse Glass: One of my mantras when I was writing at WorldChanging was that "we can't assume that all the tools we'll have for fighting global problems have already been invented." Today brings

• Turning Greenhouse Gases into Greenhouse Glass: One of my mantras when I was writing at WorldChanging was that "we can't assume that all the tools we'll have for fighting global problems have already been invented." Today brings  Bruce Sterling did me the honor of

Bruce Sterling did me the honor of  "Topsight" is one of those words that deserves wider use, especially within the scenario/futurist/early indicators community. It means a view, or understanding, of all aspects of a problem or situation: the components, the context, the drivers, the participants... everything. The Big Picture, but with less emphasis on broad structures and more emphasis on completeness. Computer scientist David

"Topsight" is one of those words that deserves wider use, especially within the scenario/futurist/early indicators community. It means a view, or understanding, of all aspects of a problem or situation: the components, the context, the drivers, the participants... everything. The Big Picture, but with less emphasis on broad structures and more emphasis on completeness. Computer scientist David

Ah, only if this were real...

Ah, only if this were real...