• Green Acres, Now With Penthouse View: Vertical farms finally make the move from cybergreen fantasy to the pages of the New York Times. The logic is seductive: urban towers, filled not with more offices and apartments, but with food crops.

Dr. Despommier estimates that it would cost $20 million to $30 million to make a prototype of a vertical farm, but hundreds of millions to build one of the 30-story towers that he suggests could feed 50,000 people. “I’m viewed as kind of an outlier because it’s kind of a crazy idea,” Dr. Despommier, 68, said with a chuckle. “You’d think these are mythological creatures.” [...]

“If I were to set myself as a certifier of vertical farms, I would begin with security,” he said. “How do you keep insects and bacteria from invading your crops?” He says growing food in climate-controlled skyscrapers would also protect against hail and other weather-related hazards, ensuring a higher quality food supply for a city, without pesticides or chemical fertilizers.

Vertical farms offer a nice way of sidestepping a big urban density problem (that is, how does a city feed itself without relying on hundreds of square miles of farmland?), and have the (to me) right balance of futurosity and plausibility.

It occurs to me, though, that a variant of the vertical farms might work well for the hollowed-out suburbs, too: how much would it cost to convert a McMansion to allow it to grow food?

• Viva, Provigil!: Are people still going on about doping in sports? That's so last year. The big new panic-trigger is doping in the workplace -- not with steroids, but with cognitive-modification drugs. Tech Crunch, as close to a bellwether of Silicon Valley angst as you can get, lets us know that entrepreneurs have come to find drugs like modafinil (sold under the brand name Provigil) can give them a professional edge. The tone is that of condemnation, of course, but at the same time implicitly letting it be known that everybody's doing it, and if you're not, you're probably falling behind.

We're seeing the same thing happen with Adderal and Ritalin in high school and college, apparently, and I wouldn't be shocked to see that practice carry over more and more into the professional world.

But here's where this all gets tricky for me: I have a prescription for Provigil, as it is legally available for dealing with "shift work sleep disorder," which includes jet lag. And it works, at least for me. I've gone as long as nearly 40 hours without sleep while traveling internationally, in meetings where I had to be able to perform at a decent level. No dozing off, no weird hallucinations from lack of sleep, just mental clarity and alertness. Provigil wears off after about six hours, and doesn't interfere with normal sleep. Go me.

This isn't meant as an endorsement, only an observation that (a) yes, these kinds of cognitive modification drugs are in the workplace already, and (b) it's a lot more complex than a simple "doping is illegal and/or bad!"

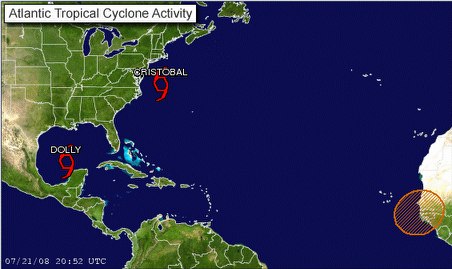

• Uh Oh: Chris Mooney, author of (among others) Storm World, notes that the early days of the 2008 Atlantic hurricane season is looking a lot more like the deadly 2005 season than the comparatively mild 2006 and 2007 seasons.

In particular, the finally dissipated Hurricane Bertha set all manner of records, most of them associated with longevity and strength so early in the season. That includes becoming the longest lived Atlantic hurricane ever recorded in July, and the third strongest ever recorded in that month (and sixth strongest overall among pre-August hurricanes).

And now we're looking at a likely Hurricane Dolly, which will get the chance to churn over the extremely warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico before making landfall somewhere (presumably) along the Mexico or Texas Gulf coast.

Meanwhile, the National Hurricane Center has just begun to track a strong tropical wave--much like the precursor to Bertha--that is emerging off of the African Coast. The strongest Atlantic hurricanes, dubbed Cape Verde-type storms, generally form from such waves--and generally do so later in the season. But that's not the case in 2008.

The National Hurricane Center is your best bet for rapidly-updated information on the status of Atlantic and Pacific storms near North America. They have RSS feeds for all of their reports, and ScienceNewsBlog pushes NHC alerts out via Twitter.

• Got a Spare $60 Million?: My old WorldChanging colleague, Vinay Gupta, has a post on his "Bucky-Gandhi Design Institution" blog entitled "How to fix the developing world for sixty million dollars," and it makes for fascinating reading. It's a lengthy argument, but it boils down to this:

So, here’s what I’m going to spend your notional sixty mil on: television programs for farmers and people who live in slums. I’m going to blow the whole lot on making 200 hours of science telly, and giving them away. [...]

But the bulk of this science telly for farmers is the basics of what you need to thrive in the developing world, in four major categories

how to grow more food?

how to stay alive? (water, sanitation, basic medicine)

what is happening in the rest of the world? (physical and economic geography, including things like futures markets)

what is happening here? (where did television come from? what’s a computer? what’s an antibiotic? what’s science? why did things start to change, what does it mean, and where will it end?)

What I love about Vinay's proposal is that it's not just the "teach a person to fish" school of changing the world -- it goes to the level of "teach a person about ecosystems, nutrition and tools, so that if fishing doesn't work out, they'll be able to figure out what to do as an alternative." Yeah, it's more complex, but the near-term stuff is also there -- but Vinay doesn't just leave it there.

Good reading, and good work, sir.

• Heads Down: I've been trying to blog more lately (and without quite as much "here's the talk/interview I did" content), but I'm looking at a pretty intense next few weeks. Lots of work on Superstruct, of course, but also a few big writing jobs -- including a major piece for the Atlantic Monthly. I'll probably be going back to 1-2/week mode for awhile.

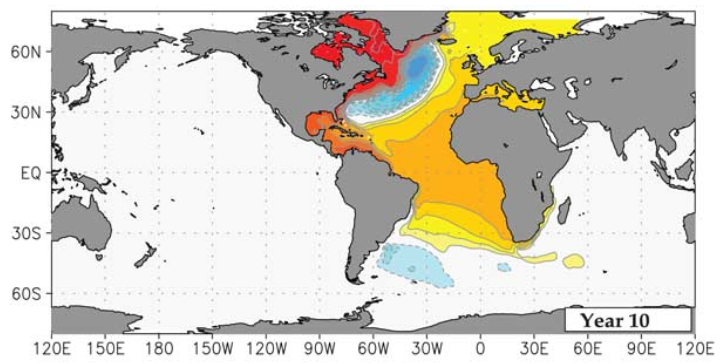

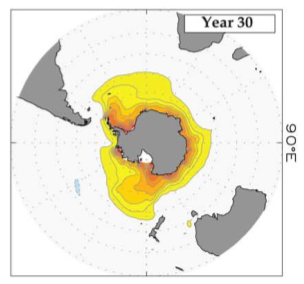

It's fascinating to watch the evolution of the mainstream media coverage of the geoengineering concept. I'm actually pretty pleasantly surprised: most of the articles I've seen have had an overall tone of caution about the proposals, even while recognizing that if we end up using geoengineering technologies, it's because things have gotten so bad that we're down to our last-ditch methods of avoiding disaster. The basics of the stories have been pretty consistent: we're in an even bigger climate mess than we thought, so real scientists have begun to consider options for climate modification that they might have dismissed in the past, simply to head off catastrophe; nonetheless, more research needs to be done. I haven't seen any news stories (as opposed to opinion pieces, or blog articles) that even imply that geoengineering would be considered a replacement for decarbonization, and I'm seeing fewer news articles that start from the perspective that such climate modification is inherently wrong, period.

It's fascinating to watch the evolution of the mainstream media coverage of the geoengineering concept. I'm actually pretty pleasantly surprised: most of the articles I've seen have had an overall tone of caution about the proposals, even while recognizing that if we end up using geoengineering technologies, it's because things have gotten so bad that we're down to our last-ditch methods of avoiding disaster. The basics of the stories have been pretty consistent: we're in an even bigger climate mess than we thought, so real scientists have begun to consider options for climate modification that they might have dismissed in the past, simply to head off catastrophe; nonetheless, more research needs to be done. I haven't seen any news stories (as opposed to opinion pieces, or blog articles) that even imply that geoengineering would be considered a replacement for decarbonization, and I'm seeing fewer news articles that start from the perspective that such climate modification is inherently wrong, period.

Okay, it's a standard presumption that global warming is going to make major heat waves more likely, in more places, lasting longer. Moreover, because of thermal inertia and climate commitment (not to mention how stubborn traditional politics seems to be on environmental issues), we're going to continue to see warming temperatures for at least a couple more decades. In short, the kind of heat I've been seeing locally over the last week -- multi-day 110°+ temperatures -- may be an increasingly common event for some time to come.

Okay, it's a standard presumption that global warming is going to make major heat waves more likely, in more places, lasting longer. Moreover, because of thermal inertia and climate commitment (not to mention how stubborn traditional politics seems to be on environmental issues), we're going to continue to see warming temperatures for at least a couple more decades. In short, the kind of heat I've been seeing locally over the last week -- multi-day 110°+ temperatures -- may be an increasingly common event for some time to come. I wrote about the "

I wrote about the "

Good googly-moogly. Just as it seemed to be settling down, the Internet drama about Xeni at

Good googly-moogly. Just as it seemed to be settling down, the Internet drama about Xeni at