In the Spring of 1990, I wrote my Master's thesis in Political Science at UC Berkeley. The paper, "Passionate Intensity: Consociational Democracy and the Civil War in Lebanon," was reasonably well-received, and after receiving my MA, I filed it away with my other papers. Recent events in Lebanon reminded me of this work, however, and I dug it out this morning.

I won't burden you with the entire thesis. It runs close to 30 pages, is written in a somewhat dense academic style, and spends a lot of time talking about the history of political organization and underlying political theory. However, the concluding section, looking at some of the dynamics that drove the collapse of Lebanon's "consociational" electoral model (in short, a structure where various sub-cultures have explicit political roles and formal bloc voting), provide some useful grounding for understanding what's happening in Lebanon right now. If you're curious about how the situation in Lebanon evolved the way it did, follow the extended entry.

[From Passionate Intensity: Consociational Democracy and the Civil War in Lebanon, by Jamais Cascio, 1990]

One of the most important components of social change in Lebanon was the alteration of the demographic balance. [...] While the Maronites struggled to maintain their power, the Shi'ites began to express theirs. Norton estimates that the Shi'ite community numbers up to one million people, making it (at thirty percent of the population) the largest sectarian group (Norton, Augustus Richard, Amal and the Shi'a: Struggle for the Soul of Lebanon, 1987:17). Like the Maronites, the Shi'ites perceive themselves to be a minority sect in the Middle East; also like the Maronites, the community is politically divided. The radical Hizb Allah movement and the more mainstream Amal organization compete for the allegiance of the Lebanese Shi'ites; whereas Hizb Allah is heavily influenced by the example of revolutionary Iran, the politics of Amal is "far less concerned with issues of orthopraxy or apostasy than with political reforms of an `ordinary' and familiar sort" (Norton 1987:13). Significantly, neither group arose from the traditional Shi'ite leadership. Both Amal and Hizb Allah grew in opposition to the conservative feudal leadership, which had long been co-opted by the government; in the fierce fighting of 1975 and 1976, Cobban reports that "so strong was the tide of Shi'i radicalism in those months that old-style Shi'i leaders such as Kamil al-As'ad and Kazim al-Khalil had to seek protection in the Maronite-held enclave throughout the war" (Cobban, Helena, "The Growth of Shi'i power in Lebanon and its Implications for the Future" in Shi'ism and Social Protest Juan R.I. Cole and Nikki R. Keddi, eds., 1986:142). Clearly, when the Shi'ite leaders hide with the Maronites out of fear of their own people, there is much room for a new generation of leadership to arise.

Changes in population growth rates are not the only sources of instability. Urbanization, education, economic disparities, and a generational change in sectarian leadership have all contributed to the demise of traditional political patterns in Lebanon.

Urbanization in Lebanon was a function of both internal migration and the influx of refugees, particularly Palestinians (Khalaf, Samir, Lebanon's Predicament, 1987:220). As discussed earlier, continued Israeli raids into the south of Lebanon resulted in a massive internal migration of the Shi'ites into the slums of Beirut, 60 percent of the southern rural population by 1975 (Nasr, Salim, "Roots of the Shi'i Movement" in Merip Reports, June 1985:11). They brought with them not just numbers, but the militancy and beliefs developed during the conflict in the south. By the 1980s, the Shi'ites dominated the once-Sunni West Beirut (Friedman, Thomas, From Beirut to Jerusalem, 1989:241). Although Lebanon in general, including the largely rural areas, displays many of the social characteristics of urbanized communities-- Norton quotes Iliya Harik as saying, "In many respects, Lebanon is one big suburb of Beirut" (Norton 1987:31)-- the uncontrolled growth of Beirut accentuated and accelerated processes of social division. In particular, Hourani cites the emergence of a "growing gap between rich and poor," in the 1960s and 1970s, "a gap which was more obvious as wealth became more ostentatious" (Hourani, Albert, "Visions of Lebanon" in Toward a Viable Lebanon, 1988:5). Khalaf also cites divisive class distinctions as a result of over-urbanization, but goes on to discuss a "peculiar feature of Lebanese urbanization: the survival of communal and traditional loyalties... In other words, the intensity and increasing scale of `urbanization' as a physical phenomena has not been accompanied by a proportional degree of `urbanism' as a way of life" (Khalaf 1987:221). In combination with sources of confessional and social fragmentation, the survival of communal loyalties meant that there could be no greater "Lebanese" identity to unify the divided groups.

Education, also typically a source of new social identity, became, like urbanization, another medium of fragmentation. As discussed earlier, educational institutions fell under the consociational rubric of subcultural autonomy. Although close to one hundred percent of primary school-age children in Lebanon attended in the late 1970s (Norton 1987:32), during the same the period calls from communal leaders for more complete sectarian control over education were becoming more strident (Bashshur, Munir, "The Role of Education: A Mirror of a Fractured National Image" in Toward a Viable Lebanon, 1988:55).

Economic disparities between the various confessional groups have their origins as far back as the 1830s, under Ibrahim Pasha and Amir Bashar II. Capitulations initially granted to the Europeans were gradually extended to the local Arab Christians. Continued discrimination throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century has left Lebanon with an economy still greatly segmented on a sectarian basis.

The Shi'a have suffered the brunt of the social and economic inequalities in Lebanon. Lebanon's Shi'ites "have long been considered the most disadvantaged confessional group in the country." The wide-spread nature of the economic and social divisions in Lebanon are vividly described by Chamie:

With whatever reasonable criterion one wishes to employ-- such as education, occupation, female labor participation, income, movie attendance, membership in associations-- the socioeconomic differentials which emerge between the religious groups are unmistakably clear: non-Catholic Christians and Catholics at the top, Druze around the middle, Sunnis near the bottom, and Shi'a at the very bottom."

(Chamie, J., "Religious Groups In Lebanon: A Descriptive Investigation", International Journal of Middle East Studies, April 1983:181)

Threats to political order arise from within a community, too. The domination by a small number of families of the political system left those outside the "club" to develop alternate political movements. The leadership of these alternate groups are typically young and not of the traditional leadership families. The membership, too, is of the `dispossessed' of Lebanon (Norton 1987:129); the traditional leaders have become irrelevant.

The combination of demographic and social shifts with the explosion of over-urbanization, non-secular education, economic discrimination, and intergenerational rivalry brought ever closer the breakdown of society. When outside forces with their own selfish interests began to use Lebanon as a playfield, that breakdown became inevitable. New movements arose and sought out their own places within the chaotic panoply of Lebanese politics. Hourani writes that

The more the various groups which make up Lebanon have entered its public life, the clearer it has become that they are moved not only by different interests and a desire to have their share in the profits of power, but also by different ideas of what Lebanon is and should be. The point of danger comes when they try to reach out beyond their sectional interests and link them with some general principle of politics and to draw from that principle a vision of Lebanon.

(Hourani 1988:7)

In short, in the words of Kamal Joumblatt, "the opium of ideology is frequently more noxious than the opium of religion" (Joumblatt, Kamal, I Speak for Lebanon, 1982:94).

Underlying the dissolution of Lebanese society was the rigidity of the governmental system. Had the National Pact addressed the possibility of change, much of the bloodshed of the last fifteen years could have been avoided. But by consecrating a particular order of sectarianism, and by being tied so intimately to the traditional leadership, Lebanon's consociational system was forced to commit a particularly violent suicide.

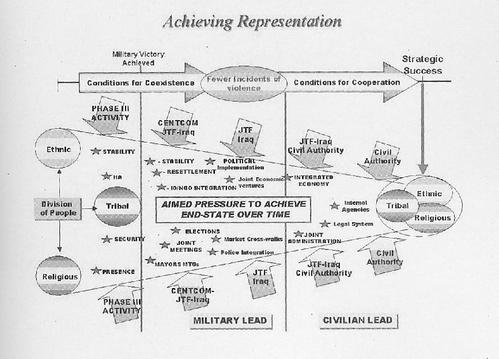

The lessons that can be drawn from the demise of Lebanese consociationalism are varied. The ability of Lebanon's system to survive for thirty years certainly is indicative of the possibilities inherent in consociational democracy. In comparison to other consociational governments, however, an important criticism comes out. In Austria, Belgium, and even to some extent Switzerland, consociationalism was not an end in and of itself; it was an important step toward building a national identity and, crucially, building inter-segmentary trust. The value of democracy is not in how a group wins, but how it loses-- knowing that it will have another opportunity to win in the near future, and that the opponent will then also accept defeat. Consociationalism, by calling for a grand coalition and an extreme emphasis on minority rights, allows that trust to develop. Lebanon never took the next step, dismantling the consociational structure to leave a genuine democracy.

The important lesson in this is that subcultural autonomy should not be allowed to control all other aspects of the political structure. There is a critical line between allowing a subculture to regulate its own members and allowing it to dictate to the national government. Obviously, part of subcultural autonomy entails the central authority giving up certain powers; the other half of this is the subculture recognizing the legitimacy of centralized rule.

In Lebanon, such a subordination of segmentary power to the national government was not possible as long as the state was seen to be a tool of a particular minority, the Maronites. A further vital lesson, then, is that a consociational democracy needs to have guarantees of proportionality that actually reflect the national composition. Whether the National Pact, at its inception, actually did that is open to debate; what is clear is that the Pact made no provisions for altering the sectarian ratios in accordance to changing demographics.

Closely related to this is the importance of co-opting new political movements into the system whenever possible. When a state is so clearly divided into rival segments, leaving any out is asking for trouble. When the electoral system itself makes entry of new groups into the government extremely difficult, whatever short- or medium-term stability gained is lost forever when the alternate movements gain a significant following, and turn to violence and rejection of state authority. The lesson of this is clear-- a consociational republic must not discourage the creation of novel political movements, unattatched to any traditional leaders, and must allow them to work with the government, and not against it.

The lessons of Lebanon's consociational democracy are apparent but not simple to follow, and may in fact be discouraging. Ethnic, linguistic, and religious nationalisms will increasingly become the methods used to express dissatisfaction with the situation; we are already beginning to see this in a number of countries. If these movements are not handled wisely, chaos seems a likely result. Lebanon was once looked upon as a model to be emulated in these matters. There seems to be little chance of peace and democracy returning to Lebanon in the near future; Lebanon, however, can still serve as a model-- of a system to be avoided.

It's the classic dilemma of both foresight and environmental consulting: how do you get the people with the power to act to pay attention? Political leaders rarely pay sufficient attention to issues of systemic sustainability and planning for long-term processes, at least before events reach a crisis. There are numerous reasons why this might be, ranging from election cycles to crisis "triage" to politicians not wanting to institute programs for which they won't be around to take credit. It's nearly as difficult to get leaders to pay attention to complex systems, with superficially different but deeply-connected issue areas. If you were to try to bring together political, business and community leaders for a day-long discussion of, say, what life might be like at the midpoint of this century, with a focus on environmental sustainability coupled with economic, cultural and demographic demands, how much support do you think you'd get?

It's the classic dilemma of both foresight and environmental consulting: how do you get the people with the power to act to pay attention? Political leaders rarely pay sufficient attention to issues of systemic sustainability and planning for long-term processes, at least before events reach a crisis. There are numerous reasons why this might be, ranging from election cycles to crisis "triage" to politicians not wanting to institute programs for which they won't be around to take credit. It's nearly as difficult to get leaders to pay attention to complex systems, with superficially different but deeply-connected issue areas. If you were to try to bring together political, business and community leaders for a day-long discussion of, say, what life might be like at the midpoint of this century, with a focus on environmental sustainability coupled with economic, cultural and demographic demands, how much support do you think you'd get?

The next five days will see a potentially interesting -- at least to me -- intersection of a variety of important dynamics I've been following closely.

The next five days will see a potentially interesting -- at least to me -- intersection of a variety of important dynamics I've been following closely. Today's Topsight Tuesday is all about things that worry and frighten us: massive asteroid impacts, terrorism, and Powerpoint.

Today's Topsight Tuesday is all about things that worry and frighten us: massive asteroid impacts, terrorism, and Powerpoint.

The life of a consulting futurist can be trying. Take next week, for example: I'll be flying off to Honolulu for five days, a guest of the

The life of a consulting futurist can be trying. Take next week, for example: I'll be flying off to Honolulu for five days, a guest of the

As

As  "The guns of August." For anyone with a background in military/political history, that phrase is redolent with sadness. It's the title of

"The guns of August." For anyone with a background in military/political history, that phrase is redolent with sadness. It's the title of