New Geoengineering Study, Part II

The article The radiative forcing potential of different climate geoengineering options is now out and available for download and discussion. As expected, it offers one of the first useful comparisons of different geoengineering techniques.

(It should be noted that the accuracy of the measurements and predicted effects of the various proposals is likely to be moderate at best; the value comes from having a clear comparison using the same modeling standards for each approach.)

In the paper, Tim Lenton and his student Naomi Vaughn, of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research and the University of East Anglia, UK, focus strictly on the radiative impact of geoengineering -- that is, how much heat absorption is prevented -- and don't examine costs or risks. The goal here is to help figure out the "benefit" half of the cost-benefit ratio. Lenton and Vaughn have another paper (to be published later this year) taking a look at the cost side, and that will be just as important as this one.

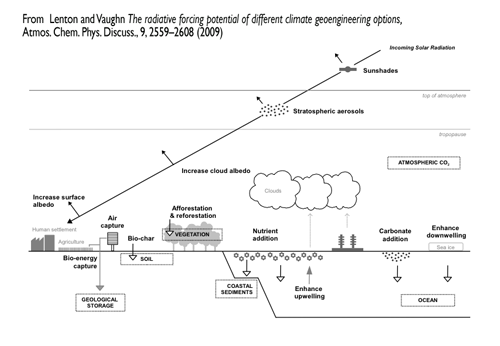

Lenton and Vaughn split geoengineering proposals into two categories:

- Shortwave options that either increase the reflectivity (or albedo) of the Earth or block some percentage of incoming sunlight. These include megascale projects like orbiting mirrors and stratospheric sulphate, as well as more localized and prosaic methods like white rooftops and planting brighter (=more reflective) plants.

- Longwave options are those that attempt to pull CO2 out of the atmosphere in order to slow warming. These include massive reforestation projects, "bio-char" production and storage, various air capture and filtering plans, and ocean biosphere manipulation with iron fertilization or phosphorus.

Lenton and Vaughn run the numbers on the likely maximum results from each of the methods, working under the assumption of simultaneous aggressive carbon cutting efforts. One thing that becomes immediately clear is that no form of geoengineering would be enough to avert catastrophe if emissions aren't cut quickly. Unfortunately, they also argue that even aggressive carbon emission cuts won't be enough to forestall disaster.

So, what works?

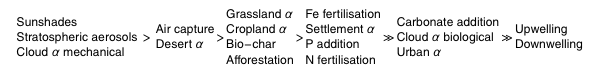

Here's the first cut analysis in a chart form:

Most effective (again, strictly in terms of radiative impact) over this century would be either space shields, stratospheric injection, or increasing cloud levels with seawater. Any of these, alone, could actually be enough to counteract global warming along with aggressive carbon emission reductions.

Next would be increasing desert albedo (essentially putting massive reflective sheets across the deserts of the world) or direct carbon capture and storage (ideally captured from burning biofuels). These would slow global warming disaster, but wouldn't necessarily be enough to stop it. Biochar, reforestation, and increasing cropland & grassland albedo come in third, half again as effective as the previous proposals; the remaining methods would be even less-effective, in some cases multiple orders of magnitude less-effective.

And all of these proposals have drawbacks. Space shields would be ridiculously expensive absent later-stage nanofabrication techniques. Stratospheric injection alters rainfall patterns, and any abrupt cessation of albedo manipulation would be worse than what had been prevented. Laying thousands upon thousands of square kilometers of reflective sheets across the desert is an ecosystem nightmare, while reforestation at sufficient levels to have an impact -- and any kind of biofuel or cropland/grassland modification -- would be incompatible with feeding the Earth's people. Carbon capture has the fewest potential drawbacks, other than cost -- and the fact that it alone wouldn't be sufficient to stop disaster, only delay it.

With the various drawbacks (which Lenton and Vaughn will examine in more detail later this year), why even consider geoengineering?

The explanation comes as an extension of the "bathtub model" Andy Revkin talks about today in the New York Times.

Imagine the climate as a bathtub with both a running faucet and an open drain. As long as the amount of water coming from the faucet matches (on average) the capacity of the drain, the water level in the tub (that is, the carbon level in the atmosphere) remains stable. Over the course of the last couple of centuries, however, we've been turning up the water flow -- increasing atmospheric carbon concentrations -- first slowly, then more rapidly. At the same time, one consequence of our actions is that the drain itself is starting to get clogged -- that is, the various environmental carbon sinks and natural carbon cycle mechanisms are starting to fail. With more water coming into the tub, and a clogging drain, the inevitable result will be water spilling over the sides of the bathtub, a simple analogy for an environmental tipping point catastrophe.

With this model, we can see that simply slowing emissions to where they were (say) a couple of decades ago won't necessarily be enough to stop spillover, if the carbon input is still faster than the carbon sinks can handle.

That said, our efforts at stopping this catastrophe have -- rightly -- focused on reducing the water flowing from the faucet (cutting carbon emissions) as much as possible. But the flow of the water is still filling the tub faster than we can turn the faucet knob (we're far from getting carbon emissions to below carbon sink capacity). Without something big happening, we're still going to see a disaster.

The shortwave geoengineering proposals, by blocking some of the incoming heat from the Sun, are the equivalent here to building up the sides of the tub with plastic sheets. The tub will be able to hold more water, although if the sheeting fails, the resulting spillover will be even worse than what would have happened absent geoengineering.

The longwave geoengineering proposals, by increasing carbon capture, are the equivalent here to clearing out the drain, or even drilling a few holes in the bottom of the tub (let's assume that just goes to the drain, too). The water will leave the tub faster, but you may have to drill a lot of holes to have the impact you need -- and drilling too many holes could itself be ruinous.

According to Lenton and Vaughn's study, the longwave geoengineering proposals would be much more effective in the long run -- at millennium scales -- than shortwave, but the shortwave would have a more immediate impact. It's clear that a combination of the two approaches would be best, of course coupled with aggressive carbon emission reductions. Build up the sides of the tub and drill a few holes, in other words.

Of all of the proposals, air capture seems to be closest to a winner here, but the costs (and technology) remains a bit unclear, and will take some time to get up and running in any event. That delay will mean pressure to use one of the shortwave approaches, too. My guess is that stratospheric sulphate injection will be cheaper at the outset than the cloud albedo manipulation with seawater, but the latter seems likely to have fewer potential risks; we'll likely try both, but probably transition solely to cloud manipulation (at least until molecular nanofabrication allows us to do space-based shielding). The various minor proposals -- reforestation, urban rooftop albedo, and the like -- certainly won't hurt to do, and every little bit helps, but alone are massively insufficient.

Lenton and Vaughn's study is precisely the kind of research that is needed to better understand what the geoengineering options are. As I emphasize here at every turn, this doesn't obviate the need for aggressive reductions in carbon emissions. But it's looking more and more like simply changing our light bulbs, boosting building efficiency, and taking a bike instead of a car, while clearly helpful, will still be insufficient to avert disaster, and even a global shift away from fossil fuels wouldn't come in time to stop the water from spilling over the edges of the tub.

Nature stopped being natural centuries ago. It's been in our hands, under our influence, for much longer than we've been willing to admit. We've got to get smart about how we're reshaping the environment -- and do so before it's too late.

A diverse assortment of legal, bioscience, psychology, and ethics academics

A diverse assortment of legal, bioscience, psychology, and ethics academics  It's an interesting historical artifact. It was the first big presentation I'd ever given, and I had to give it in front of a thousand people, including some fairly high-profile folks. I was incredibly nervous, and it shows (I really needed to stop leaning on the little podium, and would somebody please give me a glass of water!). Moreover, I read the talk, rather than just speak extemporaneously, in part because the time limit was drilled into my head, but mostly because I didn't have the confidence that I'd be able to carry off the presentation without a script. I don't do that any more.

It's an interesting historical artifact. It was the first big presentation I'd ever given, and I had to give it in front of a thousand people, including some fairly high-profile folks. I was incredibly nervous, and it shows (I really needed to stop leaning on the little podium, and would somebody please give me a glass of water!). Moreover, I read the talk, rather than just speak extemporaneously, in part because the time limit was drilled into my head, but mostly because I didn't have the confidence that I'd be able to carry off the presentation without a script. I don't do that any more.